Wraparound Blog

From Zero to 206 in 25 Years: The Wraparound Research Base Reviewed

May 09, 2017 | Eric Bruns

John Burchard

John BurchardTwenty-five years ago this month, I traveled to Burlington, Vermont to visit the campus of the University of Vermont (UVM), and considered whether to accept its offer of graduate study in community and clinical psychology.

As I learned over the next four frigid years, the sunny, 65 degree weather that greeted me that day was not something I could expect on future spring days in northern New England. What did not disappoint me, however, was my decision that day to work with John D. Burchard, Professor of Psychology at UVM. John ultimately became a mentor, friend, and my greatest role model for leading a principled, outcome-focused career and life.

When I traveled north from Virginia in 1992, John’s paper on Project Wraparound in Vermont was the only published academic paper on what were then called “Wraparound services” for youth with complex behavioral health needs and their families1. John’s trailblazing work inspired me during graduate school to study individualized, family-driven service models, and how systems can invest in such shifts in service delivery. My dissertation was the first-ever controlled study of the impact of respite care.2

As John’s health declined in the early 2000s, John, his wife Sara, and I wrote a chapter on Wraparound in a book Edited by Barbara Burns and Kimberly Hoagwood3. This experience inspired me to come back to Wraparound as a research topic, and find others with whom to further build the research base. By then, over a dozen studies on Wraparound had been published, including a couple of randomized control studies,4 5 and momentum was growing to develop and support new ways to keep youth “at home, in school, and out of trouble.”6

Where is the Wraparound research base now?

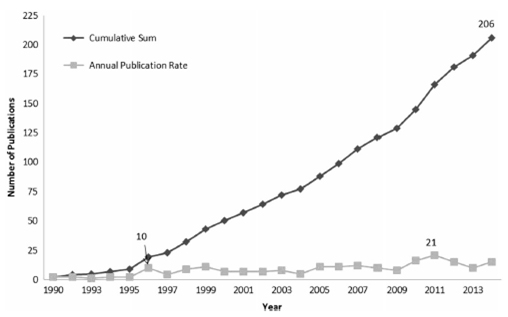

A systematic review of Wraparound research just published in the Journal of Child and Family Studies and led by Jennifer Schurer Coldiron on our University of Washington Wraparound Evaluation and Research Team found that, as of 2014, 206 peer-reviewed publications had been published on Wraparound. Below are just a few of the authors’ findings from this new review:

- The rate of Wraparound research has been accelerating over time. As shown in the accompanying figure, 10 to 20 papers on Wraparound are now typically published every year. It seems that Wraparound is far from a passing fad, as was a concern around the turn of the millennium.

- Wraparound has been the subject of 22 controlled studies, 15 of which showed positive results of Wraparound compared to the control or comparison condition. Although several studies found no differences between conditions, none of the 22 studies found better outcomes for the comparison group.

- Implementation quality and fidelity measurement has only become commonplace among published outcomes studies in the last few years. Among studies that found null results and actually measured implementation quality, lack of adherence to the Wraparound model was typically a main reason Wraparound did not improve outcomes over services as usual.

- Relatedly, an emerging body of research is demonstrating the importance of adhering to specific principles of Wraparound care in order to achieve outcomes. Research is also finding that without achieving certain types of program- and system-level standards (e.g., caseloads, training and supervision, funding flexibility), youth and system-level outcomes are likely to suffer.

- Cost-effectiveness studies are not typically conducted with rigor; however, several such studies7 make a compelling case for Wraparound’s ability to dramatically shift service use patterns toward more community based care and reduce overall costs of services.

- Eighty-four of the 206 papers on Wraparound were non-empirical “thought pieces” that described the practice model or made the case for Wraparound. Interestingly, the proportion of non-empirical papers published every year does not seem to be declining over time. We speculate that Wraparound’s capacity to serve as an “operating system” for coordinating care for many types of individuals and system contexts has led authors to continue to propose new and novel applications of Wraparound for people with complex needs. Of course, it could also be that youth- and family-driven, strengths-based care is still viewed as a “fringe” idea, one that requires continued advocacy.

Despite the growing number of publications, the review also found many gaps in our understanding that point to an array of research studies left to be done. Some topics that need more attention include:

- More on Wraparound’s mechanisms of positive change. As the human services field shifts increasingly toward system-level integration, Wraparound has a lot to offer the conversation about what care coordination practices are most important to achieving outcomes. Our team has proposed that practice elements such as being youth- and family-determined, individualized, and needs- and outcomes-based are applicable to any type of care management model, at any level of intensity. Research that explores this assertion more rigorously and systematically could greatly aid the development and support of care coordination models in all types of health care settings.

- Relationship of the service array to outcomes. While some pilot studies have asked about how best to integrate evidence-based clinical practices and Wraparound8, little rigorous study has asked about the impact of investing in specific types of services or workforce development for staff in other provider roles. Given how little attention many systems of care pay to the breadth or nature of formal services in the continuum of care, such research may help provide guidance – and motivation – to do so.

- Implications of policy, financing, staffing, administrative, and system conditions. Our National Wraparound Implementation Center (NWIC) has now provided training, coaching, and system-level technical assistance to over 10 states. As a result, we have data that indicates certain types of system structures (such as Care Management Entities9) are associated with better youth and family-level practice. Much more understanding in this area is needed to help guide system-level reforms and refinements in states and communities.

- Workforce Studies. With help from nationally renowned trainers and experts, NWIC has developed a sophisticated training, coaching, certification, and implementation support model that uses data to adjust over time. However, even we cannot be sure how best to continue to evolve this model, or how much effort is worth investing in what areas, without more rigorous research on topics such as supervision, data-informed coaching, staff selection, staff training, and methods of providing technical assistance.

- More on family and youth peer support. Remarkably, given our dedication to being youth and family driven and to incorporating youth and parent peer support wherever possible, only three of the 206 studies focused on this topic.

Although the Wraparound research base – and research base for care coordination more generally – would benefit greatly from additional study, Coldiron, Bruns, & Quick (2017) nonetheless concluded that the Wraparound literature produced to date has provided a wealth of useful information. It has explicated and tested (somewhat) Wraparound’s theory and core components, its program and system supports, and applicability across systems and populations. It has begun to unpack relations among system, program, and practice elements and outcomes.

Most important perhaps, the review suggests that we now have a reasonable basis for concluding that, when implemented well, and for an appropriate population, Wraparound is likely to produce positive youth, system, and cost outcomes. In short, Wraparound is research-based. We think John Burchard would be pleased to see how far Wraparound – and those who have endeavored to provide it and promote it – have come.

Figure 1. Annual and Cumulative Wraparound Publications

We invite you to read this review of research, and to let our team at the National Wraparound Initiative know if your Wraparound initiative or system of care provides an opportunity for us to answer any of the above questions. In the meantime, be on the lookout for future installments of this Wraparound Blog, from the National Wraparound Initiative and its many collaborators.

1. Burchard, J. D., Clarke, R. T., Hamilton, R. I., & Fox, W. L. (1990). Project Wraparound: A state-university partnership in training clinical psychologists to serve severely emotionally disturbed children. In P. R. Magrab & P. Wohlford (Eds.), Improving psychological services for children and adolescents with severe mental disorders: Clinical training in psychology. (pp. 179-184). Washington, DC US: American Psychological Association.

2. Bruns, E.J. & Burchard, J.D. (2000). Impact of respite care services for families with children experiencing emotional and behavioral problems and their families. Children’s Services: Public Policy, Research and Practice, 3(1), 39-61.

3. Burchard, J. D., Bruns, E.J., & Burchard, S.N. (2002). The Wraparound Process. In B. J. Burns, K. Hoagwood, & M. English. Community-based interventions for youth (pp. 69-90). New York: Oxford University Press.

4. Clark, H. B., Lee, B., Prange, M. E., & McDonald, B. A. (1996). Children lost within the foster care system: Can Wraparound service strategies improve placement outcomes? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 5, 39-54. doi: 10.1007/BF02234677

5. Evans, M. E., Armstrong, M. I., & Kuppinger, A. D. (1996). Family-centered intensive case management:

A step toward understanding individualized care. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 5, 55-65.

6. Rosenblatt, A. J. (1993) At home, in school, and out of trouble. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 2, 275-281. doi:10.1007/BF01321225

7. Grimes, K. E., Schulz, M. F., Cohen, S. A., Mullin, B. O., Lehar, S. E., & Tien, S. (2011). Pursuing Cost-Effectiveness in Mental Health Service Delivery for Youth with Complex Needs. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 14(2), 73-86.