Wraparound Blog Archives - National Wraparound Initiative (NWI)

Tribute to Karl W. Dennis, “The Father of Wraparound”

July 10, 2025 | NWI

This tribute is a guest post authored by Ira Lourie.

Karl W. Dennis

Karl W. DennisKarl Dennis, known as the “Father of Wraparound,” passed away on Friday June 20, 2025, after a long illness. He was 88 years old. I first met Karl in 1973 when he invited me to a conference in Chicago, but he did not get connected to the System of Care world until 1986 when we invited him to come to our first-year review meeting for CASSP, the forerunner of the System of Care Grants.

Karl was the heart and soul of this thing we call “Wraparound.” It began in the early 1970’s at a new agency for troubled kids in Chicago called Kaleidoscope. Karl was hired as Kaleidoscope’s first Executive Director in 1973 – a position he held for 27 years until his retirement in 2002. For the rest of his life, he roamed the United States and the World teaching about Unconditional Care and Wraparound. Kaleidoscope was a unique agency that was created based on an unusual philosophy of truly Unconditional Care – the trademark of which was “No Reject, No Eject”; in other words, they took any kid that was referred to them and wouldn’t kick them out regardless of their behavior. This wasn’t Wraparound as we know it today – that emerged about 20 years later. At first it was just plain Unconditional Care… caring for the kids whose lives they were caring for as if they were their own and building on the strengths of those young people and their families.

I once visited Karl at Kaleidoscope, and was placed in his office while I was waiting for him. This was a long time after the current practice of Wraparound had emerged, around the turn of the century. As I waited, I took time to look through the Kaleidoscope training manual, where I was amazed that the term Wraparound could not be found. Karl helped formulate the practice of Wraparound with other Wrap originators, such as John VanDenBerg and John Burchard, and was one of the earliest Wraparound trainers. He went to communities with emerging systems of care and gave direct family consultations in a Wraparound format, but never ran his agency that way. They practiced all the elements that now define Wraparound, but without calling it that – they called it Unconditional Care.

Karl and his wife Kathy were the Dynamic Duo of Wraparound. As one individual announced at a recent meeting, “Karl told us what to do, and Kathy told us how to do it!” She was hired at Kaleidoscope in 1990 as their new Development Officer and quickly worked her way into Karl’s heart, leading to their marriage 28 years ago in 1996. Over their years together, she and Karl worked closely together both at Kaleidoscope and after, expanding the Unconditional Care philosophy into the Wraparound modality. Kathy became Karl’s constant partner in his Wraparound training and his support of the parent movement.

Karl was an unbelievable storyteller. His Wraparound training sessions, lectures, etc., were all based on his stories of the children, youth and families he worked with over the years at Kaleidoscope. You all know those stories, or at least you should: Tyrone and Carol, the substance users who had lost their children to the social services system but whom Karl found were “great with children” and found a way to let their children get the best of their parents, with Tyrone ending up on the Kaleidoscope board of directors. Cindy, the homeless prostitute with AIDS, whom Karl reconnected to her AIDS baby. Alex, who had been thrown out of jail because he had torn an oak and steel door off of its hinges, returned home to his mother as his post jail placement. Bright, legally-blind Marcus paired up in an apartment with a not-so-bright roommate who could see, ending up with Marcus driving a car down the block into parked cars.

In 1994, I asked Karl if I could use one his stories in a monograph I was writing. Luckily, he agreed, giving me the honor “If anybody ever writes up my stories, it will be you!” So, we got a grant from the Casey Foundation to write a book and a pre-publication promise from the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA) to buy a lot of them. Which led to our co-authored book about Wraparound based on Karl’s stories, Everything is Normal Until Proven Otherwise; A Book About Wraparound, which was published in 2006. To tell you something about Karl’s giving nature, I wanted the book to be titled something related to one of Karl’s stories, but he insisted that it should be named after something that he liked of mine, Lourie’s First Law of Adolescence.

Karl was involved with the transition of Unconditional Care into formal Wraparound in the mid-1980’s, along with John VanDenBerg and John Burchard. Karl would be upset if I didn’t tell you that a major disappointment in his life was when, around 2004, the Wraparound folks removed the concept of Unconditional Care from Wraparound, replacing it with Persistence. After all, Wraparound was developed on a base of Unconditional Care, Karl would say – how could it be Wraparound without it. This, what Karl saw as a diminution of the power of Wraparound, led in 2023 to us publishing a second edition of Everything is Normal Until Proven Otherwise, this time calling it A Book About Unconditional Care and Wraparound. (Unconditional was put back into the National Wraparound Initiative’s Wraparound Principles around 2008.)

Karl believed strongly in the strengths of families and the important role that parents had to play in the care of their children. He was so invested in supporting families that he shined as a favorite of the families of troubled children (who Karl referred to as being Seriously Emotionally Unique). He traveled the country giving the developing network of parent organizations free trainings and consultations on how to work with their children. He believed that the parent movement was, along with Unconditional Care, a most important aspect of caring for children with troubles.

The national Federation of Families for Child Mental Health gave their major professional award to Karl and then named it after him. Karl bonded with those parents and their state, local and national organizations. He believed strongly that parents were the key to understanding the special needs of their children and were vital in their care; such as in the case of Tyrone and Carol where, while they were not fully able to be the primary caretakers, Karl recognized their important role in the lives of their children. In his story about Alex and his mother (to whom we gave a name, Shirley, in the 2nd Edition), Karl led her as she developed the intervention approach needed to keep Alex at home. Karl supported parent groups at all levels throughout his career, and as I look at the list of his mourners, I believe parents might outnumber professionals. Three of his closest friends from the system of care days up until to his death were parents: Sue Smith, Patty Derr, and Dixie Jordan.

Karl was an open advocate for civil rights, women’s rights, and sexual diversity rights, among others. He came from a mixed genetic background that basically included everybody. He was extremely proud of the Native American part of his heritage and thrived on Native philosophies and culture, and especially art. Those who had the opportunity to visit Karl and Kathy’s home could feel that in their décor. He was the most inclusive person I’ve ever met. Karl was part of the small group that came together to define the extremely broad concept of Cultural Competence for the Child and Adolescent Service System Program (CASSP), which later became the System of Care grant program.

Karl had a unique understanding of human nature and could almost instantly bond with anybody. Even in his first encounters with people who were experiencing problems, he had a unique ability to make jokes about what was going on with them without offending them – using those jokes to bond with them. A great example of this was with Cindy, who I mentioned before, the mother of the AIDS baby, a woman with AIDS who had been living on the street and had been prostituting herself in order to exist and who accepted Karl’s invitation for her to see her baby which had been taken from her by the state. When Cindy and Karl first met in the halls of Kaleidoscope, she had an odor and whispered to him an offer to give him some sexual favors. Karl’s response was, “We need to get you a bath and some teeth in your mouth before we can even talk about that.” After a brief tense moment, she began to laugh and then they laughed together; ultimately she and Karl worked well together and became friends.

Karl never put himself first. I remember well the time we were with a group at some meeting and a large group was getting ready to go to dinner, and the prevailing desire was to go to a well-known barbeque place. Karl was a vegetarian (well, really a pescatarian), and some of us pointed out that this might not be the best dinner choice for Karl as a pescatarian. We began to move toward making a different dinner choice, at which point Karl spoke up and said, “I’m sure they had fish last time I went there. Let’s go.” When we got there, we found that fish was only on the menu on certain other days, but as the rest of us began to struggle with what to do next, Karl quickly announced that he would be fine with just sides. Maybe a better story about Karl’s selflessness and humor was one in which Ira, a short Jewish-looking Jew, and Karl, a tall black man, were walking together down the streets of Sandpoint, Idaho, which was famously known for being the home of the Skinheads. Karl looked at me and said, “If they hassle you, tell ’em you’re with me!”

We all loved Karl, and he loved us all back. Karl taught us humility and tolerance, inclusion and support, and Karl taught us to look for the best parts in everyone. He taught us to be better people as we tried to emulate his ideals. Knowing Karl made me a better person, and I think that is probably true for all of us who knew him, interacted with him, and loved him.

There are thousands of reasons to bless Karl and miss him, and I’ve only touched a few… Thank you Buddy, we Love you and miss you so much.

New Research Shows Hospitable Organizations and Systems Are Critical to High Quality Implementation of Wraparound

March 22, 2025 | NWI

Because Wraparound is a system-level intervention that requires policy and funding changes and cross-system coordination, successful implementation requires purposeful action by provider organizations and the systems within which they are embedded. As a result, Wraparound has been observed to take more time to implement than many other types of evidence-based treatments (EBTs) for youth with complex behavioral health needs. But how long does implementation typically take? And what factors affect the pace and quality of implementation?

The Wraparound Evaluation and Research Team (WERT) has just published a research article in Psychiatric Services (available online beginning March 27, 2025) that confirms Wraparound takes longer to implement than other EBTs. The study also showed how specific activities within organizations and systems influence both the amount of time it takes to implement Wraparound as well as the completeness and quality of implementation.

This study examined implementation in 10 states that used one of two state-level administrative structures to implement Wraparound: Care Management Entities (CMEs, 4 states) and Community Mental Health Centers (CMHCs, 6 states). We used the Stages of Implementation Completion (SIC) tool to assess the degree to which each state completed organization-level and system- or state-level activities that are necessary to implement Wraparound, along with the amount of time it took to complete them. 1 In addition, we gathered fidelity data with the Coaching Observation Measure for Effective Teams (COMET) to assess the degree to which Wraparound was implemented with adherence to its underlying practice model.

Results showed that states that used CMEs completed more implementation activities than states where Wraparound was provided by CMHCs. States that used CMEs also implemented the majority of activities more quickly and had higher mean fidelity scores as measured by the COMET than CMHC states.

Compared to other complex cross-system EBTs, Wraparound took significantly more days to implement pre-implementation activities (560 days compared to 336 days for other EBTs) and implementation activities (959 days compared to 712 days). Importantly, differences between Wraparound and other EBTs were smaller for CME states.

Which activities take the longest? The study showed that system-level activities (such as engaging state leaders) and organization-level activities (such as conducting implementation reviews) account for much of the slow pacing of implementation.

Finally, the team asked whether the pace of implementation activities influenced fidelity. Interestingly, analyses showed that taking longer to complete pre-implementation activities (such as identifying stakeholders and gaining their buy-in and developing detailed implementation plans) was associated with better Wraparound fidelity. Conversely, states that took longer during the implementation phase (e.g., hiring staff, establishing systems to monitor fidelity) showed significantly poorer fidelity.

The findings of this study indicate that interventions with a strong systems-level focus, such as Wraparound, require considerable time to implement. However, a hospitable administrative structure (in this case using a CME) helped shorten the time and resulted in better adherence to the Wraparound practice model.

Results also showed that states that take time early in the planning process to organize systems and providers and develop clear implementation plans implement care of higher quality and are more expedient in later implementation stages.

All these results underscore the importance of careful planning and management of system and organizational level activities required to make Wraparound implementation happen. For a high-level overview of these details, you can see the NWI’s monograph on Wraparound Implementation Standards. For more intensive support to system-level implementation of care coordination, the National Wraparound Implementation Center uses a technical assistance process and associated measures that focus on key activities organized by the same three implementation phases: Pre-Implementation, Implementation, and Sustainment.

By creating strategies to facilitate coordination of implementation activities within and across these contexts, administrators and providers can facilitate provision of better Wraparound and other supports for our young people and their families.

1 The SIC assesses implementation activity completion and timeliness across eight stages that are organized into three phases: pre-implementation (e.g., initial planning, practitioner training); implementation (e.g., services initiated, ongoing coaching delivered); and sustainment (e.g., using data systems to measure costs and outcomes).

New Analyses Shine Light on National Trends in Wraparound Fidelity

February 23, 2025 | NWI

The origins of “Wraparound” as a term for team-based, family- and youth-driven care coordination are not 100% clear. But we do know that Wraparound’s roots go back at least 40 years, if not more.

During those 40-plus years, Wraparound’s use has expanded substantially in the U.S. and globally. More and more systems of care are also using standardized measures of quality and fidelity, helping grow Wraparound’s evidence base. Wraparound is now being used for many types of individuals with complex needs – not just youth and families.

Reference to Wraparound as a service model and system strategy seems to be ever-increasing across the U.S. and the world. But what is happening with respect to Wraparound fidelity and outcomes? Is Wraparound heading in the right direction?

Last month, the National Wraparound Implementation Center (NWIC) hosted a webinar at which the University of Washington (UW) Wraparound Evaluation and Research Team (WERT) presented results from a new analysis of over 4,400 surveys of parents and caregivers using the Wraparound Fidelity Index, Short Form (WFI-EZ). These results, presented with additional detail, are also available in a new report from WERT.

Data were collected by 132 sites in 31 states and large systems of care across the U.S. While UW WERT has analyzed its national fidelity dataset before, these are the first such results since the COVID-19 pandemic. Among some of the findings:

- Wraparound fidelity falls short of established benchmarks. The “national mean” for the WFI-EZ Total Fidelity score was found to be 71% of total possible fidelity. However, based on analyses of fidelity scores that achieve positive youth/family outcomes, UW WERT has proposed a benchmark for “high fidelity” of 80%, and a benchmark for “adequate” total fidelity as 75%.

- Caregiver satisfaction was found to be 79% of total possible – above the benchmark for “borderline” (75%) but well below the benchmark for “high” satisfaction (>92%).

- While many states and local initiatives struggle to implement Wraparound with high or even adequate fidelity, others were found to exceed “adequate” and reach “high” fidelity. Thus, the “national means” found in these analyses do not necessarily reflect the range of implementation quality being achieved across different states and systems, many of which are doing an admirable job.

- Caregiver perceptions of fidelity are trending in the wrong direction. National means for total fidelity and for three of the five Wraparound key elements are lower than the last time we analyzed our fidelity results (2017). The decline in average total fidelity (from 73% to 71%) suggests that Wraparound implementation has worsened overall. Ongoing research by UW WERT and NWIC will aim to identify what may be causing this decline. Are policy and fiscal environments becoming less hospitable? Is it turnover and other workforce stressors? Or something else?

- Certain critical indicators of Wraparound fidelity were found to be particularly low. Items assessing meaningful engagement of natural supports, having the right members on Wraparound teams, teams’ understanding of families and their needs, and purposeful transition planning were all lower than average for the WFI-EZ overall.

- Caregiver-reported institutional placement decreased, but use of emergency departments for mental health problems rose 31%. These and other trends in outcomes found from these analyses results mirror current trends in youth and family systems of care, including lack of availability of both institutional and community-based services.

UW WERT will continue to feed such results back to the field, including results of surveys of youth and care coordinators, as well as from other fidelity measures such as the Document Assessment and Review Tool (DART). Along the way, the NWI and NWIC will continue to try to make sense of these results and use them to improve our support to the national Wraparound community.

In the meantime, we invite you to read this new report and ask how your organization or system of care might use its own data to identify areas for improvement and work together with your partners to achieve them. No matter how ambitious the benchmarks for “high fidelity” may seem, the current report shows that high-fidelity Wraparound can be achieved. Training and Technical assistance from groups like NWIC and UW WERT can help get your program or system there.

When it comes to improving outcomes for youth and families, however, outside help can’t substitute for visionary leaders and community partners working together to do whatever it takes to build effective systems. Our most vulnerable youth and families deserve nothing less.

New Results from Document Assessment and Review Tool (DART) Further Demonstrate Importance of Wraparound Fidelity

December 15, 2024 | Eric Bruns

For over a decade, the National Wraparound Implementation Center (NWIC) and UW Wraparound Evaluation and Research Team (WERT) have been promoting “high-fidelity” Wraparound practice in their training, technical assistance, evaluation, and continuous quality improvement efforts.

Why is this our “true north”? Because we believe, now more than ever, that it is critically important to honor youth and families’ strengths and preferences, engage their natural and community supports, tailor the supports they receive to their individualized needs, and other elements that define Wraparound practice.

We have also found via many evaluations and research studies that Wraparound fidelity as measured by our Wraparound Fidelity Assessment System is associated with more positive family – and system – outcomes.

Now NWIC and UW WERT have uncovered additional evidence for the importance of fidelity from the newest measure of the WFAS: The Document Assessment and Review Tool (DART)

We analyzed documentation from 1,150 youth/families in seven states using the DART. Results showed that the majority of fidelity domains assessed by the DART were significantly associated with youth and family outcomes, such as residential stability, improved mental health and interpersonal functioning, regular school attendance, and avoiding arrests and behavioral health crises.

We also found additional evidence for the importance of supporting Wraparound fidelity – and the validity of the DART. Our analyses showed that states that have been implementing Wraparound longer and with better-developed training, coaching, and system supports scored significantly higher on the DART fidelity and outcome scales.

As we have done for the Wraparound Fidelity Index (WFI-EZ), results from these analyses will also help DART users interpret their results across all DART domains, including Timely Engagement, Meeting Attendance, Driven by Strengths and Families, Natural and Community Supports, Needs-based, Outcomes-Based Process, Key Elements, Safety Planning, and Outcomes.

To see more on these and other results from these new analyses, we invite you to attend our January 13th webinar: “What Are the National Means?… and What Do They Really Mean? Data Insights from WrapStat.”

In this webinar, we will present data from thousands of fidelity assessments collected via the DART and WFI-EZ. We hope that results from these analyses will help us understand what areas of fidelity are most challenging to achieve and point to benchmarks for Wraparound states and initiatives that use the DART to evaluate success and stay on track.

As always, our overarching goal will be to continue to feed data back to our national Wraparound community of practice, and help licensed users of WrapStat and the WFAS measures make the most of these tools.

See you in January!

Eric Bruns and the NWIC and UW WERT teams

2024 Top NWI Web Pages and Publications

December 4, 2024 | NWI

As the end of the year approaches, we’re reviewing information about visits to our website. This helps us make decisions about the new products and website updates that we will work on in the coming months.

In the past year, the NWI’s website has seen an average of just over 4,300 visits per month. In total, visitors viewed an average of about 5,500 pages per month, and downloaded about 580 documents. Top pages and downloads included key foundational articles, such as those describing the Wraparound principles and the phases and activities of the Wraparound process, as well as new blogs and other content. More specifically…

Top newer content includes:

- The new, completely revamped version of The Wraparound Process User’s Guide: A Handbook for Families (also available in Spanish)

- Reviews of the research on Wraparound—including the new 2024 research summary

- Recordings of recent webinars (and registration for upcoming ones)

- Regularly updated “News from the Field”

- Blogs generally, including one from earlier in the year titled What do Staff Say About Turnover in Wraparound?

- The NWI Spotlight, which features stories of people making the Wraparound principles real

Most viewed and downloaded classic content includes:

- Foundational content on Wraparound basics (also in Spanish), principles, phases and activities, and implementation

- The NWI library of tools and documents

- Information about fidelity and practice quality

- Wraparound videos

Moral Injury and Our Youth and Family Workforce

November 2, 2024 | NWI

Moral injury is a condition that can occur when an individual “bears witness to, perpetuates, or fails to prevent” an event that violates their values or beliefs.

Moral injury was originally described as a type of trauma experienced by military personnel. But in her excellent book, If I Betray these Words, Wendy Dean, MD, elegantly describes how moral injury can also be experienced by physicians who are forced to violate their sacred oath: To put the needs of patients first.

What leads to moral injury among doctors? In America’s current healthcare system, healthcare workers are increasingly forced to put the priorities of insurers, managed care, electronic health records, and other entities before the needs of the people they are treating.

The impact has been tragic: Thousands of our most talented and dedicated physicians are leaving the practice of medicine. Family practice doctors working in underserved and rural communities are the most likely to be injured – both financially and morally.

Because they are least able to return a profit to their employers and to insurers, these practitioners who are most desperately needed are also the ones who are most likely to abandon their calling.

Unfortunately, these repetitive insults also afflict members of our youth and family behavioral health workforce. Whenever a clinician has to spend more time with an EHR than with a family, or a peer support specialist cannot find a provider who could meet a family’s needs, or a care coordinator is denied $100 in flexible funds to get a youth in an after-school program, we risk moral injury. When these injuries amass, these invaluable members of our workforce can be driven to leave the field.

We often use the term burnout to describe this phenomenon. But as Dr. Dean describes, “burnout” suggests a lack of resilience, a problem that lies within the individual.

Moral injury is a more accurate term for this escalating tragedy. Moral injury locates the source in our systems – our fiscal and policy structures – and in the profit-driven forces that we have allowed to dictate the kind of care we provide.

What can we do to build systems of care that can forestall or even reverse this affliction? There are policy and financing strategies that have been shown to promote better care for youth and families. Our team’s research on care management entities, for example, has shown that more innovative, flexible, and tailored policy and financing mechanisms at a system level are associated with better fidelity to the Wraparound principles, and thus, better care for youth and families.

We believe that these system- and provider-level strategies also can help our care providers feel more effective at providing families with the help they need – which is the calling that led them to enter the field in the first place.

Currently, researchers affiliated with the National Wraparound Initiative are asking these questions, and many others, with a national study of the Wraparound workforce. We are asking hundreds of providers in dozens of provider organizations what keeps them going… or what makes them contemplate leaving.

In the coming months, the National Wraparound Implementation Center will also be hosting a series of webinars on these topics, including a session on state- and system-level strategies to achieve better adherence to the Wraparound principles and high-quality systems of care.

Also in the Spring, we will present the results of our workforce study, with implications for states and provider organizations.

And, all the above will be presented and discussed at July’s bi-annual Training Institutes, at which you can attend sessions on these topics and much more.

Across all these events, our youth and family workforce will be a common theme. We believe that part of holding managed care and provider organizations responsible for high-quality care to families includes providing supportive working conditions for their staff.

One way or another, we are all responsible for preventing the infliction of moral injury on the invaluable resource that is our care providers.

Community is Central to the Philosophies of Wraparound and Systems of Care

July 23, 2024 | Eric Bruns

We strive to keep young people, even those with the most intensive and complex needs, in their homes and communities. And communities need to pull together and collaborate on behalf of these families if they are to succeed despite the many obstacles they face.

As Coretta Scott King once said, ““The greatness of a community is most accurately measured by the compassionate actions of its members.”

Those who work on behalf of these families need community and compassion as well. Care coordinators, case workers and family partners can be buoyed by seeing families overcome seemingly impossible barriers and achieve their hopes and dreams.

At other times, of course, barriers borne of poverty, addiction, past trauma and systemic racism can threaten to undo all the progress.

Organizational and system leaders need community action to overcome their own highs and lows. For some, grants are awarded, followed by the struggle for sustainability.

For others, the thrill of a community taking Wraparound to scale is undermined by layers of managed care bureaucracy. Increasingly, cost savings from Wraparound that once were re-invested in community services are now funneled as profits to an unseen few. Red tape and perverse cost-cutting incentives force programs to compromise the principles of flexible, family-driven and individualized care their program worked years to build.

When the youth and family movement was young, and systems of care and Wraparound were radical and exciting new paradigms, such highs and lows were experienced within communities full of risk-takers and innovators. People across all levels of service provision were all “in it together.”

State and national events helped inspire and reinvigorate. But especially since the COVID-19 pandemic, we have had fewer opportunities to come together in person as local, state, and national communities of care. When state and local finances are tight, such events are the first to get cut from budgets. Meanwhile, national events have been postponed, curtailed and ended.

For all the above reasons, it was thrilling for us to see the spirit of the Wraparound community living, breathing and thriving in the sun of Southern California.

June 12-14, four members of the National Wraparound Implementation Center attended California’s Partnerships for Wellbeing Institute, a mile from Disneyland in Anaheim. Organized and hosted by the center of excellence at UC Davis with multiple state child-serving agencies, this year’s Partnerships conference theme was “People, Purpose, Passion: Promoting Equity, Family and Community.” I can personally say it lived up to its billing.

2024 Partnerships for Wellbeing Institute Attendees from NWIC/WERT. Click image to open larger version

Partnerships for Well-Being (PWB) is an annual event that aims to promote new skills, build networks of support by learning with and learning from one another, and elevate relationships with families, informal supports and professional partners. The event did all of the above and more.

For this veteran of the “Wraparound Family Reunions” of the 1990s, PWB felt like a homecoming. Folks from all over the state mingled, networked, presented, learned and were inspired. For a few days at least, my cup, which can feel pretty empty at times, was proverbially filled.

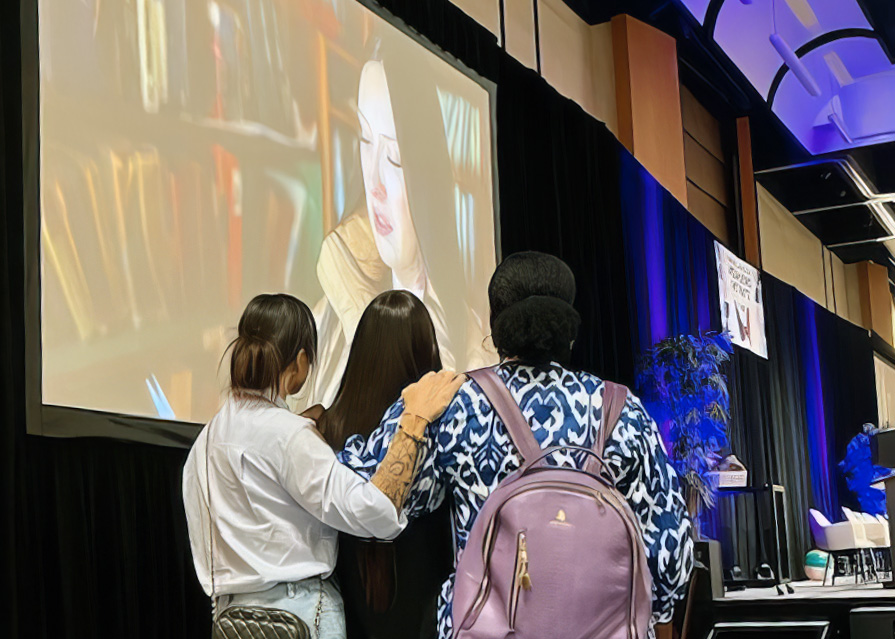

Panel at the 2024 Partnerships for Wellbeing Institute. Click image to open larger version

As is typical, the most inspiring programming was provided by families and youth themselves, who told their story of healing to over 1,000 people.

Among these family members was a parent named Harmony, whose first child, Little Bear, was removed from her home due to the multiple stresses in her life.

But with help from her community’s Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) representatives, peer support, and the unconditional care from her grandmother and other family members, Harmony is now on a path to wellness and caring successfully for her second child – who was in the audience at the Conference.

You can experience some of the magic of the event by watching “Harmony’s Story,” one of two family stories on the website of the UC Davis Center for Excellence in Family Finding and Engagement.

Family watching the film ‘Harmony’s Story.’ Click image to open larger version

The California event reminded us all how much we all need collaboration and community in our work. As one Californian, Cesar Chavez, said, “We cannot seek achievement for ourselves and forget about progress and prosperity for our community… Our ambitions must be broad enough to include the aspirations and needs of others, for their sakes and for our own.”

We at NWI implore you to brainstorm with your colleagues, peers, and supervisors ways you can come together to build and strengthen your community.

For a national event that can do the same, we also invite you and your team to attend the 2025 Training Institutes, hosted by the Innovations Institute, July 6-10 in National Harbor, Maryland.

Whether it is at a national, state, or local level, or even just within your own organization, we know of no better way to remind ourselves that helping meet the needs of others can be done not just for their sakes – but also our own.

Bridging the Wraparound Gap: How FOCUS Works for Families with Less Intensive Needs

June 14, 2024 | NWI

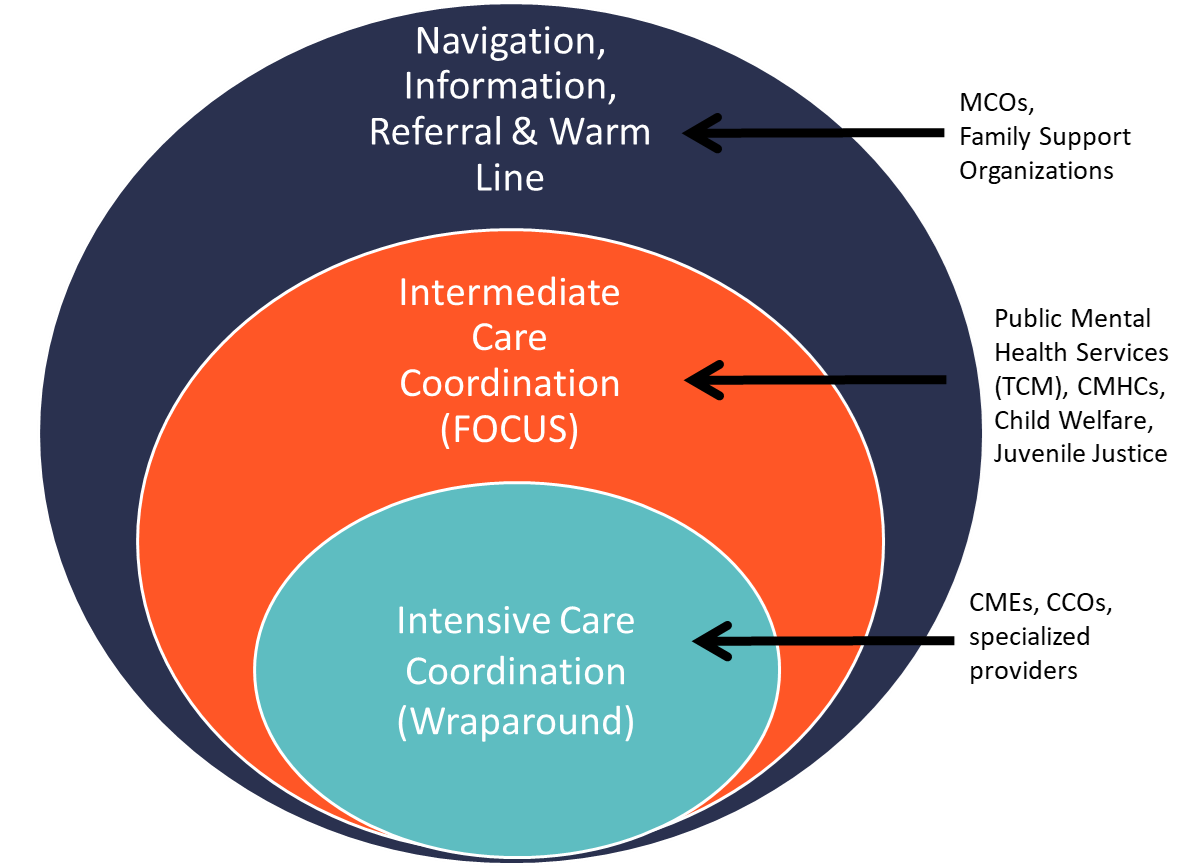

Research has consistently shown that Wraparound care coordination can help keep youth with the most complex needs “at home, in school, and out of trouble,” while also reducing strain on caregivers, and reducing costs from out of home placements. As a result, families and state and local systems of care leaders alike often advocate for intensive care coordination programs that adhere closely to Wraparound principles. But what does care coordination look like for families of children and youth with less intensive needs?

To build “tiered” systems of care coordination that can be right-sized to the diverse needs of families, an increasing number of states and localities have sought support from the National Wraparound Implementation Center (NWIC) to implement care coordination at intermediate levels of intensity. Meanwhile, leaders in other settings, such as schools, have found that intermediate care coordination is more feasible to implement with available staff (such as school social workers) compared to intensive, full-fidelity Wraparound.

For such goals and service settings, NWIC, and the Innovations Institute at the University of Connecticut, have developed FOCUS, a model designed to bring the benefits of care coordination to families with complex – but less intensive – needs.

FOCUS modernizes traditional case management models by integrating a person- and family-centered care value base with empirically supported practice elements shown to improve engagement and outcomes for youth and families. The model supports decreased system involvement while working to build connections and supports for families through community-based resources. As an intermediate care coordination model applicable across behavioral health, child welfare or juvenile justice systems, FOCUS is a key component of a three-tiered care coordination approach:

- Wraparound for youth with the most intense needs,

- FOCUS at the intermediate (or tier 2) intensity, and

- Family navigation (i.e., information, warm referrals and handoffs) for children and youth with lower intensity needs.

Figure 1. Levels of Need Served by Systems

Click image to open larger version

Systems implementing FOCUS provide right-sized community-based and family-centered care coordination that is a better fit for a youth and family’s unique constellation of strengths and needs. The FOCUS care planning process prioritizes an authentic partnership with the family and results in the development and continual refinement of a plan of care, based on active tracking of targets such as progress toward outcomes, achievement of the family’s vision, and satisfaction.

For FOCUS, fidelity is grounded in four key elements that is demonstrated by the care coordinator across each of the phases of the FOCUS planning process:

- family-anchored

- individualized

- accountable

- comprehensive

Examples of family-anchored practices include the cultivation of an authentic partnership with the family starting with information-gathering (e.g., learning from the family what has worked in the past and what might be helpful), capturing ratings from the family around their satisfaction and progress, and modifying the plan accordingly.

Individualized practices build from the uniqueness, skills, interests, hopes, and desires of each person in the family.

Accountable speaks to the care coordinator’s role in monitoring services and supports for completion, impact and satisfaction. The care coordinator might demonstrate accountability by openly discussing progress with the family, as the plan is reviewed and adjusted often to ensure the plan serves the family’s needs.

Comprehensive means that the care coordinator accesses community options and evidenced based practices, planning around all areas of need including medical needs. The FOCUS care coordinator includes multiple perspectives in the planning process and attends to outcomes across systems and environments.

Where does FOCUS come in? In addition to focusing on the family and its needs, the FOCUS care coordinator’s activities ensure…

Families are experiencing meaningful connections. Research tells us that positive relationships are necessary for healing, so positive interactions between family members are prioritized and elevated.

Outcomes are being tracked to ensure the things that cause the family the most pain are indeed getting better.

Coordination of the planning process means that everyone connected to the family works toward a common goal.

Unconditional positive regard is demonstrated – children, youth and their families are genuinely accepted no matter what.

The process is Short-term, with the goal of quickly building sustainable connections between families and their community’s resources, and minimizing system reliance.

The goal of FOCUS is to ensure that the care coordination workforce across child welfare, behavioral health, juvenile justice and/or education are well-trained and consistently demonstrating best practices as they achieve sustainability of FOCUS across their states, agencies, and/or organizations.

In Washington State, the Wraparound Evaluation and Research Team (WERT) evaluated FOCUS as an option for use in schools, in a project funded by a federal research grant from the U.S. Department of Education. Preliminary evidence has shown FOCUS to be feasible and well-received by parents of elementary students who were served.

We look forward to reporting back to the NWI community on the progress of FOCUS (especially as it sits alongside Wraparound), including results of evaluation aimed to continually improve the model.

For more information about FOCUS or the Innovations Institute’s comprehensive support for state-wide dissemination and installation of FOCUS, visit the Innovations Institute online or by email at FOCUSinfo@uconn.edu.

Coming in 2025

The University of Connecticut School of Social Work and Innovations Institute will unveil the FOCUS Certificate Program, an opportunity for agency teams to receive training and individualized coaching towards fidelity model practice at the frontline, supported by quality supervision and oversight.

Upcoming Webinar to Spotlight Wraparound Evaluation Methods

April 8, 2024 | NWI

Each state and community’s system of care aims to achieve the same thing: To provide children and youth with the support they need to live and thrive in their homes, schools, and communities.

And yet, each system of care is unique, with varying approaches to financing services, collaborating across agencies and providers, training and coaching frontline staff, identifying and enrolling families in services, and much more. Such variation allows researchers such as those affiliated with the NWI empirically examine what factors are associated with quality and fidelity as well as outcomes.

Each system of care’s approach to evaluation is unique as well. Although the NWI and its partners encourage use of certain tools to stay on track, such as the measures of the Wraparound Fidelity Assessment System (WFAS), states, communities, and provider organizations all invest in different methods to collect and use data.

A few examples: Some states and systems may require local counties or contracted providers to collect and report data, while others invest in a state center of excellence to do much of the work. Some states and systems emphasize measuring fidelity for individual staff persons’ coaching and professional development while others are committed to getting information to inform improvement at the system and program level. Some evaluation teams invest in family and youth leaders to collect data, while others use evaluation staff or students.

The University of Washington Wraparound Evaluation and Research Team (UW WERT) learned this firsthand just last week, as we attended a Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) conference hosted by California’s Department of Social Services. At the conference, WERT team members co-presented with representatives from DSS and four different Wraparound providers on an exciting new Wraparound initiative that aims to pilot test a comprehensive approach to evaluating Wraparound using WFAS tools and its accompanying web-based data system, WrapStat.

Because every state and system does things differently – and such decisions are not easy ones – the UW WERT is pleased to host a webinar on April 16 featuring leaders from four states’ Wraparound evaluation initiatives – one from each time zone!

Join us as representatives from West Virginia (Marshall University), Illinois (Department of Social Services), New Mexico (Children, Youth and Families Department), and Oregon (Portland State University) describe their unique approaches to evaluating Wraparound and systems of care in their state, including:

- Decisions around setting up evaluation cycles for instruments such as the Wraparound Fidelity Index (WFI-EZ), Team Observation Measure (TOM), and Document Assessment and Review Tool (DART) management – One point person for all providers vital. Share how cycles set up, parameters for selecting sampling.

- Ideal sample sizes for regular fidelity data collection.

- Tips for engaging families and maximizing response rates

- Staffing, hiring, and resourcing evaluation

- Training and certifying reviewers on the DART

- How the fidelity, satisfaction, and outcomes data are used, such as for professional development with individual care coordinators as well as provider and systems levels

- Engaging leaders at the system and provider level to review and use the data

Thanks to our presenters, and to all in the NWI community who can join this lively discussion about data!

Understanding Turnover in the Behavioral Health Workforce: What the Research Says

March 5, 2024 | NWI

Across the country, we frequently hear that Wraparound providers have difficulties with workforce retention, recruitment, and re-training. The important role of the care coordinators and supervisors is undeniable. Yet, the behavioral health workforce’s longstanding issue with high turnover rates had led to far-reaching implications, further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The National Wraparound Initiative and the National Wraparound Implementation Center have begun a new project examining turnover in Wraparound—including its causes and impacts, as well as strategies to address it. An early step in this project has been to review existing relevant research. A summary of this review is now available in a new paper on the NWI website.