Wraparound Blog Archives - Page 2 of 5 - National Wraparound Initiative (NWI)

NWI Quick Survey Findings: What do Staff Say about Turnover in Wraparound?

February 3, 2024 | NWI

Staff turnover in child- and family-serving mental health agencies has negative impacts on quality of care and outcomes, and undermines staff morale. What is more, the cost of replacing a worker is typically about 20-30 percent of annual salary, placing a burden on agency finances.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, research found that public mental health services typically experienced turnover rates of at least 20–30 percent. New research shows that turnover across the behavioral health workforce increased during the pandemic and has remained higher overall than pre-pandemic levels.

In 2017, the National Wraparound Initiative studied turnover among care coordinators, and produced a report examining turnover rates, causes and remedies. Now, post-pandemic, a team from the University of Connecticut’s Innovations Institute will be leading a new research initiative to re-examine the topic. As a first step to inform the new initiative, the NWI team put together a short, informal survey to gather initial thoughts from the field. We received 272 complete responses.

There were two main goals for the survey. First, we wanted to get a basic sense of where the biggest challenges lie. This information will help us prioritize the areas for further examination in our upcoming research. This blog will cover what survey respondents said about biggest challenges.

The second main goal of the survey was to encourage respondents to share their more detailed thoughts about various aspects of turnover, including causes and possible solutions. Many respondents provided thoughtful responses to the open-ended questions on the survey, and the research team will take time to consider these in depth as we develop our strategy for next steps.

Survey Findings

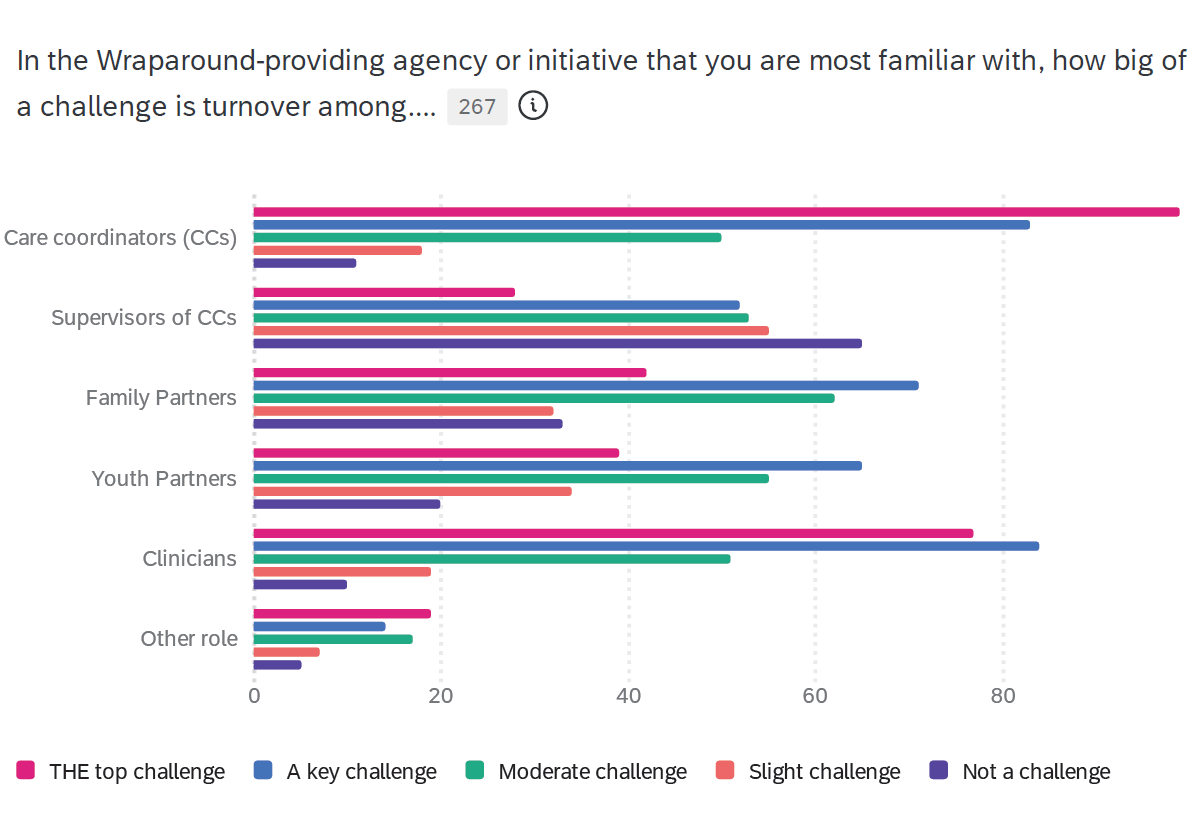

In comparison to other roles within Wraparound, turnover among care coordinators was seen by respondents as the most serious challenge. More than a third of respondents (38%) identified turnover among care coordinators as the top challenge within their agency or initiative, and almost another third (32%) rated it as a key challenge. Regarding other roles, turnover among clinicians was seen as the second most serious challenge, while turnover among supervisors of care coordinators was seen as the least serious challenge.

Figure 1. Challenge of turnover among various Wraparound roles

Click image to open larger version

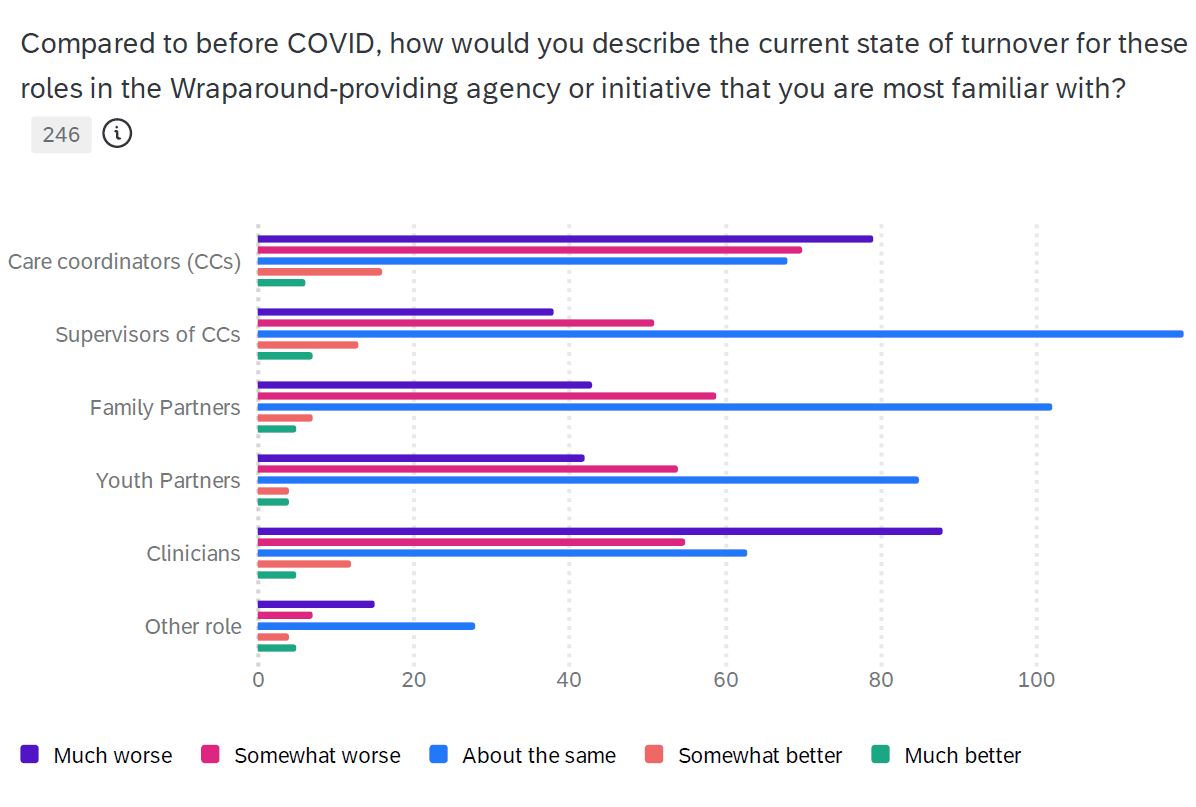

On average, across all roles in Wraparound, respondents saw turnover as a bigger problem now than prior to the COVID pandemic. Respondents saw the situation with turnover worsening most among clinicians, with 39% describing the situation as “much worse” and 25 % describing it as “somewhat worse.” Turnover was seen as worsening to a similar extent among care coordinators, with 34% of respondents saying the situation was “much worse” and 30% saying it was “somewhat worse.” In both cases, of course, that left the remaining respondents saying that the situation was the same or even better as compared to before the pandemic.

Figure 2. State of turnover among various Wraparound roles post-COVID

Click image to open larger version

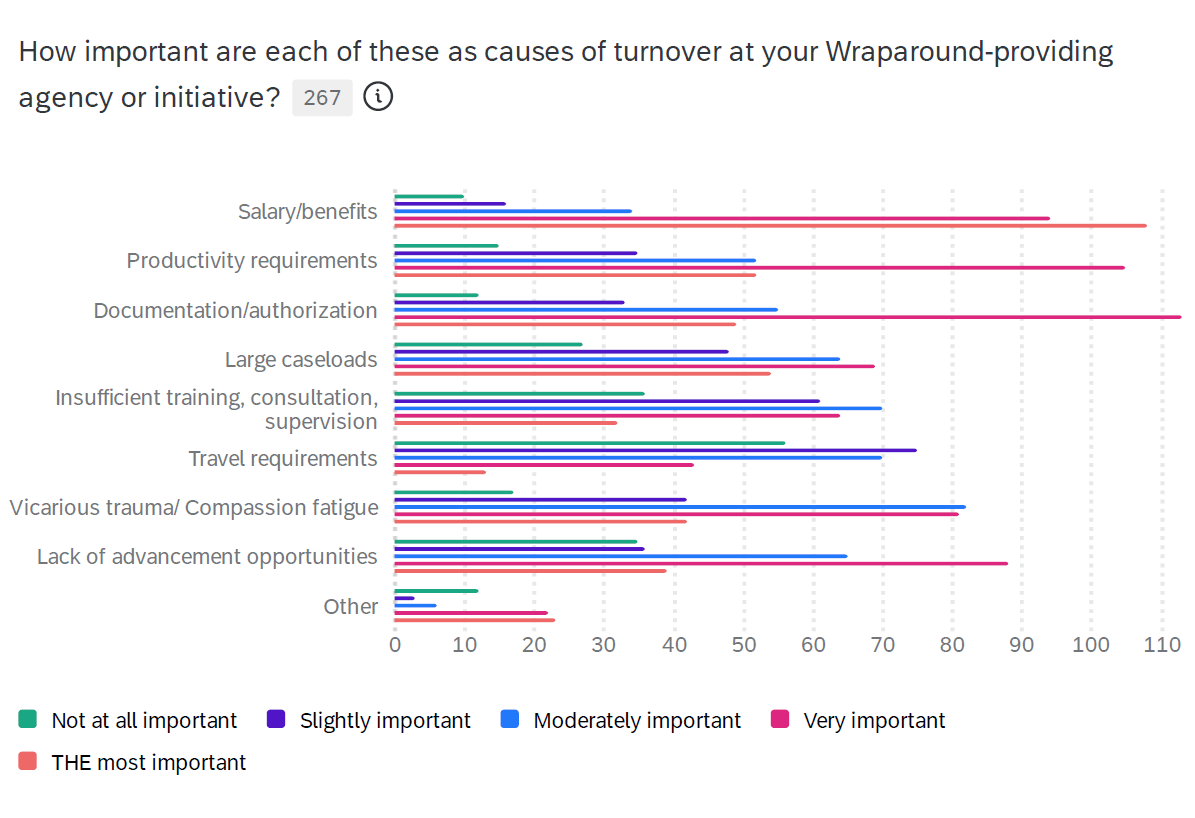

Salary/benefits was seen as the top cause of turnover, with 41% of respondents seeing it as the most important cause and 36% seeing it as a “very important” cause. Documentation/authorization and productivity requirements had similar ratings as the next most important causes of turnover. Productivity was seen as the most important cause by 20% of respondents, and as a very important cause by 41%. The ratings for documentation/authorization were 19% most important and 43% very important.

Figure 3. Reasons for turnover among staff in Wraparound-providing organizations

Click image to open larger version

More than half of the respondents reported that their agencies had taken substantial steps in an effort to address turnover. In fact, 21% said their agency had taken “important steps,” while another 37% said their agencies had taken “some” meaningful steps. In their comments, a number of respondents said that their agencies had been able to increase pay and/or provide periodic retention bonuses. Others described policy changes or enhancements to electronic record keeping that led to decreasing the burden of documentation. In addition, there was a large number of suggestions offered by respondents in their open-ended comments at the conclusion of the survey. In the coming months, the NWI team will continue to examine the challenges related to turnover, and to draw on the accumulated wisdom held by the Wraparound workforce across the nation to develop better information about the challenges associated with turnover, and possible solutions. Many thanks to all of you who responded to the survey for helping us get started with this work!

Top NWI Web Pages and Publications

October 30, 2023 | NWI

In the past year, the NWI’s website has seen an average of just over 4,200 visits per month. In total, visitors viewed an average of about 9,500 pages per month, and downloaded over 1,000 documents. Top pages and downloads included key foundational articles, such as those describing the Wraparound principles and the phases and activities of the Wraparound process, as well as new blogs and other content. More specifically…

Top newer content (within the last year) includes:

- Our report on an NWI survey that asked “Is Wraparound losing its soul?” and related blog post on the same topic

- Recordings of recent webinars (and registration for upcoming ones)

- Regularly updated “News from the Field”

- Blogs generally, including the most recent one on PEARLS, a new model for parent peer support

- The NWI Spotlight, which features stories of people making the Wraparound principles real

Most viewed and downloaded classic content includes:

- Foundational content on Wraparound basics (also in Spanish), principles, phases and activities, and implementation

- The NWI library of tools and documents

- Information about fidelity and practice quality

- Wraparound videos

Innovations Institute Unveils PEARLS: A New Model for Parent Peer Support

September 24, 2023 | NWI

By Kim Coviello and Toni Donnelly

Peer-led services and supports have become a well-established component of systems of care for all types of individuals with complex needs. This trend has only accelerated as more and more research is published showing just how effective peers can be at promoting positive outcomes – and in response to the serious workforce crises confronting health and behavioral healthcare.

Parent peer support partner (PPSP) programs are a critical component in the comprehensive service array within a youth- and family-serving system of care. However, as for many other types of evidence-based practices, PPSPs must be trained, coached, supervised, and supported to provide support that is of high quality and based on principles of effective peer support.

The Frameworks that Support the PEARLS Model for Parent Peer Support Partners

The PEARLS PPSP model was developed by the Innovations Institute at UConn School of Social Work, in collaboration with Pat Miles. The model articulates and supports the work of PPSPs through comprehensive training and coaching. PEARLS outlines authentic and purposeful parent peer support based on two frameworks:

The first framework is the parent journey that focuses on and builds from each parent’s unique experience rather than from a system perspective.

The second framework consists of six core meta-skills that form the acronym PEARLS. These core meta-skills are demonstrated in each interaction with a parent for high quality PPSP work to occur:

- P: Establish a Peer-Based Relationship: A PPSP finds ways to establish, nurture and maintain relationships with parents that are based in the spirit of peer principles. This means that the PPSP works to understand each story while finding unique ways to build a strong connection based on strategic self-disclosure and shared experience. The PPSP is responsible for establishing that relationship. The highly skilled PPSP can establish that relationship with each individual parent they are supporting, even when this is challenging. The PPSP understands the parent journey framework and uses this tool to “meet the family where they are,” and can estimate the right fit and match of support in conversation with the parent/caregiver. The skilled PPSP is able to demonstrate the six guiding principles of a trauma-informed approach in all relationships with families.

- E: Encourage Parents to Grow in their Own Decision Making: The PPSP is concerned about building connection rather than forcing change. A PPSP is not a parent corrector or responsible for communicating to parents in a way that cause them to change. Instead, a skilled PPSP takes responsibility to understand the parent’s position and empower the parent to understand their own position. By providing purposeful and strategic support, the PPSP can empower the parent to make changes they want to make, rather than convincing them to make changes that others may want the parent to make.

- A: Active Acceptance: PPSPs communicate a sense of active acceptance to, and about, the parent, even when they find personal choices to be challenging. This sense of active acceptance becomes critical as the parent moves through their system journey. If the parent’s experience is grounded in shame or a sense of being judged, they are unlikely to experience a sense of empowerment. PPSPs communicate active acceptance and recognize the difference between acceptance and agreement.

- R: Respect: PPSPs build skills to continually hold the parent they are supporting with a sense of respect. This occurs in interactions with the parent, and also occurs in interactions about the parent. For example, a PPSP may find themselves participating in staff reviews with others working with the family. During those interactions, the PPSP works to communicate that sense of holding the parent in respect when interacting with others. This establishes a relational stance of respect from others to the parent. The PPSP also works to establish that sense of respect in the parent themselves, about their own choices and sense of identity. Building capacity for respect of self is a key responsibility of a highly skilled PPSP.

- L: Link with Others in Collaboration and Problem Solving: Parent peer support always happens in the context of other services. The PPSP may be the only person who has a primary focus on the parent while other service providers are concerned about the child/youth. This can result in the parent being viewed as secondary to the concerns of the child/youth. Most parents are quite comfortable with this as they search for resources and resolution for their child. The work of PPSPs involves not only focusing on the parent but recognizing that for the parent to maximize their sense of wellbeing, they will need to actively interact with others involved in providing care and service to their family. Working together establishes a sense of family wellness and recovery, rather than simply managing or eliminating symptoms. A skilled PPSP recognizes that effective parent peer support will work better when in a cooperative, solution-focused environment.

- S: Suspend and Interrupt Bias and Blame: Bias about parents exists in communities and in systems. An anti-parent bias is evident in many child- and family-serving systems. In some cases, this bias can be traced to a genuine concern about the well-being of the child. Even when the source of the bias is grounded in a positive frame such as concern for a child’s well-being, the skilled PPSP works to interrupt bias and blame. A highly skilled PPSP will interrupt that bias and blame as a learning experience, rather than simply shutting it down. This assures that the bias does not simply become hidden but instead is removed as a barrier to building strong connections.

The PEARLS Training and Coaching Certification Program

The PEARLS training and coaching certification program is designed to leverage these two central concepts to provide the parent peer workforce with the skills needed to deliver high quality, purposeful support to parents/primary caregivers of children/youth receiving services.

To date, the PEARLS coaching certification has been implemented by the Innovations Institute in several sites and communities, as well as statewide in Maine via their new Center of Excellence. In Maine, individuals with lived experience as a parent of a child/ youth with emotional, behavioral, and/or mental health needs who have received services for their child/youth will be hired as coaches and will participate in the PEARLS coaching/training certification program.

In Maine and beyond, the goal will be to help ensure that the parent peer workforce is well trained in best practices and supported to achieve sustainability of parent peer support across the state. We look forward to reporting back to the NWI community on progress with PEARLS, and evaluation results aimed to continually improve this new model.

For more information or to connect for training and coaching, contact Innovations Institute via our website or by email at pearls@uconn.edu

New Research Study Sheds Light on Reliability, Validity, Potential Improvements, and Underlying Theory of the WFI-EZ

July 25, 2023 | NWI

By Jonathan Olson and Eric Bruns

University of Washington Wraparound Evaluation and Research Team and National Wraparound Implementation Center

Research consistently shows Wraparound care coordination promotes better residential, school, and mental health outcomes for youth with complex needs than services as usual (Olson et al., 2021). However, as we frequently discuss on blog posts, reports, and other transmissions from the National Wraparound Initiative (NWI), high-quality, model-adherent Wraparound service delivery is critical to assuring Wraparound provides this boost to child and family-serving systems “as usual.”

To help assure Wraparound quality and fidelity, the University of Washington Wraparound Evaluation and Research Team (UW WERT) has provided access to the Wraparound Fidelity Index, Short Version (WFI-EZ) for over 10 years. The WFI-EZ and other measures of the Wraparound Fidelity Assessment System (WFAS) aim to help Wraparound Provider Organizations (WPOs) assess the degree to which the core components of Wraparound are actually being used in practice. Over the past decade, more than 15,000 caregivers, care coordinators, youth, and Wraparound team members have completed a WFI-EZ survey.

Despite its widespread use, however, a published study of the psychometrics, reliability, and validity of the WFI-EZ has not previously been available – until now.

The Journal of Child and Family Studies (Bruns, Olson, Parigoris, Parker, & Walker, 2023) has published a new study examining the psychometrics of the WFI-EZ. The study had three aims:

- First, to determine if the underlying factor structure of the WFI-EZ actually aligns with the underlying structure that UW WERT has used to summarize WFI-EZ results; that is, the four key elements of the practice model promoted by the National Wraparound implementation Center (NWIC), plus a fifth focused on being data-informed.

- Second, to assess the reliability of the measure via internal consistency, agreement across caregiver and care coordinator versions of the measure, and a small test-retest reliability study.

- Finally, we assessed validity by comparing WFI-EZ scores for groups that should differ, such as WPOs with higher versus lower Wraparound climate or systems with and without training and coaching.

In the following paragraphs, we provide a brief overview of findings and their implications. For additional details, readers can also read a copy of the full paper as published in JCFS.

Methods

The WFI-EZ is a brief self-report survey, with versions for parents/caregivers, care coordinators, youth, and team members. All versions include a Section A with four items that assess fundamental elements of Wraparound practice: Presence of a team, a plan of care, regular meetings, and decisions driven by families. In addition, all respondents complete 25 items (Section B) that assess Wraparound fidelity. These items are organized into 5 subscales that correspond to the NWIC practice model: effective teamwork, natural supports, needs-based, strengths-driven, and data and outcomes-based.

Caregivers and youth complete four additional questions (Section C) that assess satisfaction with the Wraparound process. Finally, the caregiver and care coordinator forms include 9 items (Section D) that assess outcomes such as caregiver strain and resilience, and youth residential, school, and justice outcomes.

Study Methods

UW WERT analyzed data from 10,955 caregivers and 6,088 care coordinators within 243 WPOs in 25 states that were entered into WrapStat (the web-based data entry and management system for WFAS measures) and its predecessor, WrapTrack. Data collected between 2011-2021 were analyzed for this study.

In addition, 26 caregivers and care coordinators completed the WFI-EZ twice over two weeks to assess test-retest reliability. Finally, we used program-level data from 15 WPOs in one state to assess “known groups validity.”

Analyses included exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and paired-sample and independent-sample t-tests, as well as calculation of intraclass correlations (ICCs) and Pearson’s (r) correlations.

Results

WFI-EZ reliability and validity

As summarized below, results supported the reliability and validity of the WFI-EZ. However, analyses revealed some opportunities for improvement.

- The total WFI-EZ index showed excellent internal consistency (alpha = .92), meaning that its items are well-related to an underlying construct (i.e., Wraparound fidelity). The original five subscales showed borderline to high (.54 to .84) internal consistency, indicating these subscales also generally can be used reliably, with some potential room for improvement.

- Test-retest data showed excellent two-week agreement for caregivers (.92). However, reliability was only acceptable for care coordinators (.74).

- Results of validity tests indicated that average WFI-EZ scores were significantly higher for groups that would be expected to be higher. For example, total WFI-EZ fidelity was significantly higher for youth who received services that met the basic definition of Wraparound (as assessed by Section A). Caregivers with higher satisfaction with their care and their progress (Section C) also showed significantly higher average fidelity ratings. Finally, caregivers who received services from WPOs with higher organizational readiness to implement Wraparound reported significantly higher average fidelity scores on the WFI-EZ.

Factor Structure of the WFI-EZ

Results from our EFA revealed four factors rather than five. Moreover, these factors did not completely align with the original subscales of the WFI-EZ, defined as per the NWIC model.

- Although factors tapping into planning, teamwork, and natural supports were found, a fourth factor emerged that comprised 10 items from across the original five factors that seemed to relate to intermediate outcomes of Wraparound, including enhanced family assets and effective services and supports.

- While some of these items were from the original Outcomes-Based subscale (e.g., “Wraparound has given me confidence as a caregiver”), others came from the Natural Supports (e.g., “Wraparound has helped us get more support from friends and family”) and Needs-Based (e.g., “Wraparound connected my family to community supports I found valuable”) subscales.

- The internal consistency (reliability) of the new, empirically-derived subscales showed better internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and cross-informant agreement than the original subscales.

- Finally, some WFI-EZ items did not load on any of the empirically-derived factors, and had low item-total correlations. These items could thus be characterized as not adding value to the WFI-EZ overall.

Implications for Wraparound Evaluation and Practice

Together, the findings of this study provide evidence that the WFI-EZ is a reliable and valid measure of Wraparound implementation and fidelity. As described above, the total index and the original theoretically-derived subscales show acceptable levels of internal consistency and test-retest reliability. The measure also results in higher average scores for groups as would be expected – e.g., WPOs with stronger organizational readiness and caregivers who reported experiencing better satisfaction with their family’s progress.

However, results suggest that there is also room to refine the WFI-EZ to make a good measure even better. Other study results help provide guidance for how best to use the WFI-EZ – for research, evaluation, and quality improvement.

Alternative ways of reporting WFI-EZ results

The current five domains of the WFI-EZ align with the practice model on which our NWIC colleagues train and coach. We were pleased to find that these subscales were adequately reliable and valid, and to be largely reflected in the results of the exploratory factor analysis.

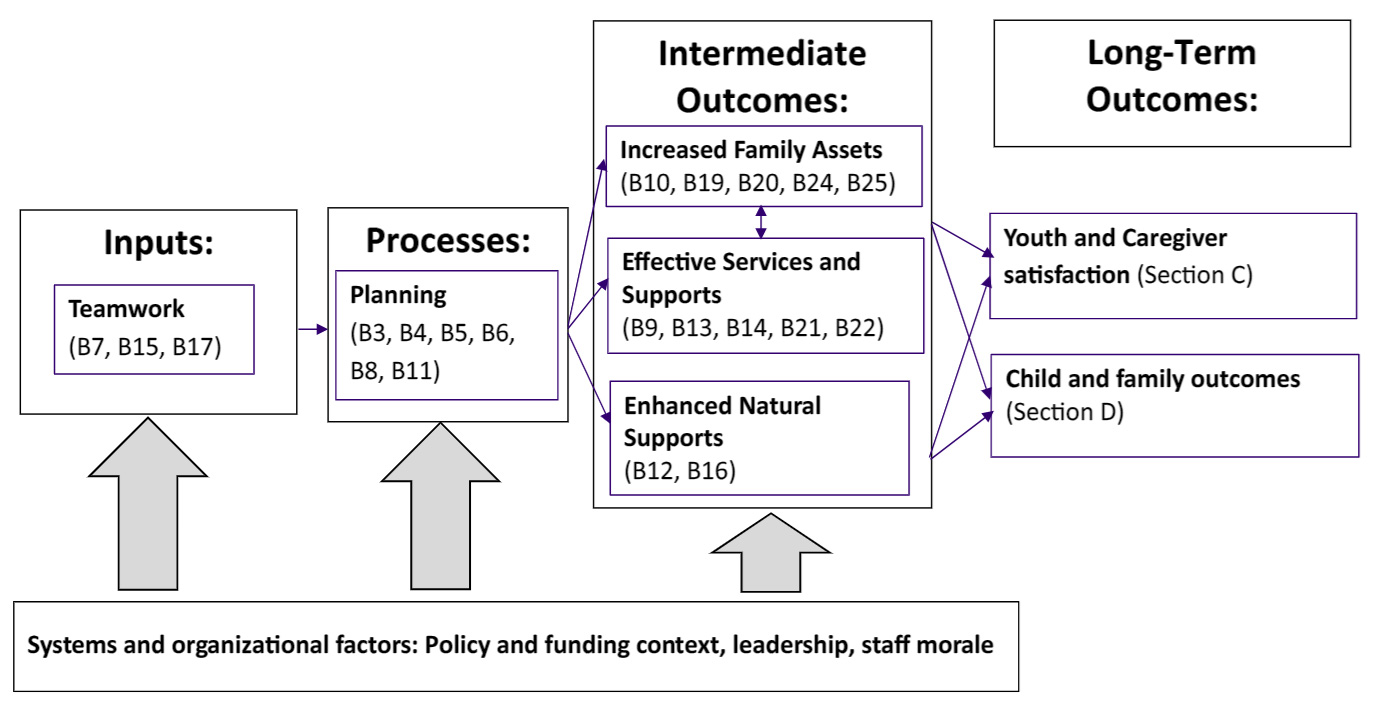

- At the same time, however, the subscales that were found via the EFA provide an intriguing alternative structure for WFI-EZ data that aligns with longstanding Wraparound theories of change. Walker and Matarese (2011) theorized that effective teamwork is critical to managing a planning process that results in intermediate outcomes such as enhanced natural supports, increased family assets and more effective services and supports. This aligns well with an alternative way of organizing WFI-EZ data that emerged from the EFA, which found factors related to planning, teamwork, natural supports, and intermediate outcomes. Taking this idea further, items from the proposed “Intermediate outcomes” domain can be further broken down into enhanced family assets and effective services and supports.

- All these factors are assessed by the WFI-EZ, and all are proposed to lead to long-term outcomes for Wraparound-enrolled youth and families that are also assessed by the satisfaction and outcomes sections (C and D) of the WFI-EZ.

- Thus, the current study reveals an intriguing alternative way of summarizing results. The figure below shows a way in which these study-derived factors may be organized. This framework may be explored in future research by UW WERT or others, and/or used by WFI-EZ collaborators to summarize their process and outcomes with data.

Figure 1. Theory for implementation and effectiveness of Wraparound as assessed by items and domains of the Wraparound Fidelity Index, Short Form (WFI-EZ)

Click image to enlarge

Guiding evaluation planning

Among many other actionable findings, the study revealed that WFI-EZ data from care coordinators may be less reliable than for caregivers. This discrepancy is perhaps not surprising, given that parents and caregivers are immersed in only one Wraparound episode – their own – while care coordinators support many families over months and years, potentially reducing their recall – and thus, the reliability of their assessments. UW WERT typically recommends that, when faced with limited resources, Wraparound initiatives and WPOs prioritize data collection from caregivers, to assure their voice. These results provide another, data-informed, rationale for prioritizing caregiver report.

Revising the WFI-EZ to reduce burden and increase reliability

As described above, four WFI-EZ items did not load on the new factor structure. Removal of these particular items also resulted in better internal consistency of the overall measure. Other items were found to contribute little variance above and beyond other items, and thus may be considered duplicative. Thus, UW WERT is considering a possible revision to the WFI-EZ to increase reliability, which would have an added benefit of shortening the tool and reducing respondent burden.

Conclusion

Until such revisions are made, however, users of the WFI-EZ can be confident that the current version of the tool is a psychometrically sound measure of Wraparound fidelity and implementation, and that subscales presented in reports generated from WrapStat summarize the data in ways that are reliable and valid. UW WERT looks forward to continuing to analyze data from the many hundreds of WPOs that license the WFI-EZ and other measures of the WFAS.

We will continue to report back results, refine our measures, and use the data to better understand implementation and outcomes of Wraparound. It is only by helping you achieve your mission on behalf of youth and families that we can achieve ours.

Nationwide Data Insights from WrapStat

June 14, 2023 | NWI

WrapStat data can show us how sites differ in terms of types of youth and families enrolled, length of enrollment, level of fidelity and satisfaction, rate of progress, and reasons for discharge. By putting all these data together, we can learn what factors might be associated with fidelity and outcomes.

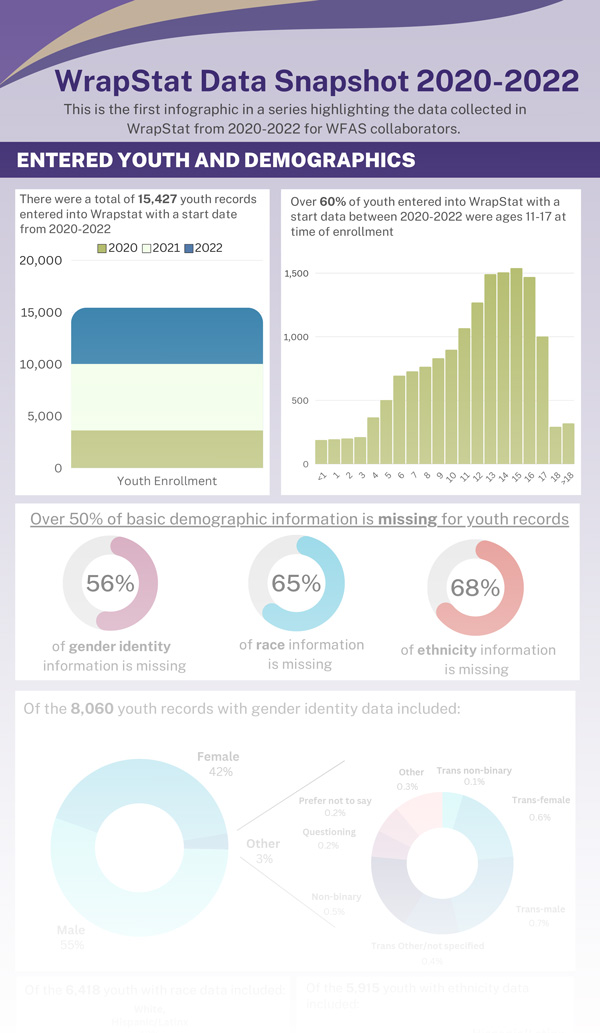

We invite you to check out the accompanying infographic that summarizes what we learned. As you can see, there were some interesting findings:

- WrapStat collaborators have been making new entries into their youth rosters steadily since WrapStat’s launch in 2020 – approximately 4,000 youth in 2020, 7,000 in 2021, and 5,000 in 2022.

- The median age of youth entered into WrapStat is 15. Over 60% of youth entered into WrapStat were ages 11-17 at time of enrollment.

- Of the 6,418 youth with race data included, 53% identify as White. Eighteen percent identify as Black, 12% Latinx, 7% Mixed race, 3% Native American/Alaska Native, and 1% Asian. Seven percent identify as belonging to another racial/ethnic group or preferred not to say.

- Critically important, WFAS collaborators are not consistently entering demographic data such as race into WrapStat. Two thirds of entries are missing race and ethnicity data and over half do not include the gender of the youth. Such a pattern compromises our ability to learn about whether, for example, racial differences in fidelity, satisfaction, or outcomes may exist in Wraparound systems of care.

- Similarly, only half of youth rostered in WrapStat have a discharge date, and of those, only 60% have a reason for discharge entered into the system. This means that, as of now, despite having nearly 19,000 youth entered into WrapStat, we only have discharge data for about 30%.

- On the positive side, our initial analysis illuminates just how much data we now have on domains such as caregiver- and youth-reported fidelity and satisfaction, and Wraparound team membership and processes. From 2020-2022, 9,715 WFI-EZ and TOM 2.0 forms were entered into WrapStat, with 2022 being the greatest year for data collection.

UW WERT and NWI will continue feeding data back to our national Wraparound community of practice. We will examine trends in Wraparound implementation nationally, and identify ways licensed users can contribute to the collective quest to use data to continually improve Wraparound – locally and globally.

New Animated Video for Families Helps Wraparound Data Collection in West Virginia

May 21, 2023 | Eric Bruns

Youth with complex needs and their families depend on systems, organizations, and practitioners to provide timely, engaging, high-quality services. As such, measuring timeliness, engagement, fidelity – and most importantly, outcomes – is critical to making sure systems, programs, and practitioners are actually delivering effective care.

However, we also know that collecting data on these things is difficult. Getting input from youth and caregivers is particularly challenging given all the demands on their time.

In West Virginia, the statewide Wraparound initiative is committed to collecting – and using – data on outcomes, fidelity, and provider and system readiness. As part of this effort, West Virginia has an impressive effort underway to collect youth, caregiver, and practitioner data using the Wraparound Fidelity Index, Short Form (WFI-EZ).

Hubbed at the statewide Center of Excellence for Recovery at Marshall University, West Virginia uses the WrapStat system from University of Washington Wraparound Evaluation and Research Team to systematically maintain a roster of all Wraparound-enrolled youth across nearly 30 providers and multiple funding streams. Marshall then uses WrapStat’s automated systems – plus a clear plan and hard work – to get WFI-EZ data with a good response rate that assures the data is reliable, valid, and useful to meet their information needs.

The evaluation team just unveiled a new component of their statewide Wraparound evaluation plan. Lydia Shaw, M.S., TCOM and Wraparound Fidelity Coordinator at the Center of Excellence used the online program Vyond to create a 2-minute video, which explains the WFI-EZ survey process for caregivers and staff in clear, accessible language, complete with animations.

As described by Ms. Shaw, “we at Marshall University wanted to make sure to explain the WFI-EZ in a way that was easily understood by all who complete surveys in WV. We have used Vyond in the past as a means to create bite sized animated informational videos and decided this would be a great route to go for our WV Families.”

According to Lydia and her colleagues, after they created the video, it wasshared with Care Coordinators and added to the Family Instructions Forms that are shared with families randomly sampled to receive surveys. When necessary, Care Coordinators also show the video to selected families to help them complete the Caregiver WFI-EZ forms.

Lydia and the team in West Virginia encourage others to use their video as inspiration. We hope other states will share their own innovative methods to encourage data collection and use with us at the NWI and UW WERT as well!

Beyond Psychotherapy and Medication: Wellness, Wellbeing and Fun Interventions

April 20, 2023 | Janet Walker

A new research review from Pathways RTC has information with important implications and reminders for young people, families and providers involved in Wraparound. The review is entitled Beyond Psychotherapy and Medication: Wellness, Wellbeing and Fun Interventions Should be Part of Robust Systems of Care for Youth and Young Adults.

The title captures the general argument of the review, which covers key portions of the vast research literature that demonstrates positive impacts on mental health from interventions that directly promote wellness, wellbeing and fun. The review highlights findings showing mental health impacts among young people experiencing anxiety, depression and other mental health conditions. These interventions run the gamut from aerobic exercise, resistance training, dance, hiking and surfing; to yoga, meditation, mindfulness, deep breathing and participation in music and the arts. There is also promising evidence from a systematic review of “behavioral activation” interventions, which promote participation in pleasurable activities generally.

Some of the studies covered in the review included qualitative findings showing that youth and young adults had strong preferences for these kinds of interventions as compared with traditional mental health therapies or medication.

Just to be clear, these activities are not add-ons to more traditional mental health interventions, they are mental health interventions. In many cases, these interventions had similar or even greater positive effects than mental health treatments like psychotherapy and medication. What is more, these are interventions that can be delivered by “lay” providers or peers, which is an advantage given the current acute shortage of mental health providers.

When implemented well, Wraparound provides a mandate and the resources to support youth and family participation in community-based recreational and social activity. And yet, as compared to the effort expended on organizing more traditional forms of therapy, only a relatively tiny proportion of a Wraparound team’s time and attention is typically focused on promoting engagement in recreation or the arts, or activities focused on wellness, wellbeing or fun. Plans that do address recreational or social needs often have what appear to be perfunctory, off-the-shelf goals and strategies, like purchasing a family gym membership or providing vouchers for movie tickets.

What if, instead, Wraparound teams devoted more significant amounts of time, effort and creativity to planning for ongoing involvement in community-based activities that young people and families look forward to, and that deliver wellbeing and joy? The principles of Wraparound certainly support this, and it is clear from research that it would contribute meaningfully to more positive outcomes for youth and families.

Wraparound and FFPSA… One Year Later

March 10, 2023 | NWI

It is hard to believe it has been over a year since “Intensive Care Coordination Using a High Fidelity Wraparound Process” (i.e., Wraparound or High Fidelity Wraparound ) was added to the inventory of research supported programs by the Title IV-E Prevention Services Clearinghouse. This made Wraparound eligible for Title IV-E reimbursement under the Family First Prevention Service Act (FFPSA).

Since this announcement, the trainers, consultants, and evaluators working under the auspices of the National Wraparound Initiative, National Wraparound Implementation Center, and the newly relocated Innovations Institute at the University of Connecticut, have been increasingly fielding requests from states and Wraparound provider organizations for help. States who included Wraparound in their FFPSA five year plans are now realizing that meeting federal expectations for evaluation and continual quality assurance may need to be more stringent and specific than expected.

As detailed in our guidance document on how to meet FFPSA evaluation and CQI requirements, state or local evaluations of Wraparound do not need to meet criteria for a rigorous experiment (e.g., random assignment or comparable comparison group). However, evaluation plans do need to be capable of providing meaningful information that can help keep the state and/or local providers on track, in areas such as:

- Population of focus: Are youth and families being served consistent with the goals for the program?

- Implementation: Are necessary system and program supports that ensure successful implementation and outcomes (e.g., staffing ratios, timely engagement, workforce training) in place?

- Is adequate quality and fidelity of Wraparound being achieved?

- Are families experiencing positive outcomes? Are youth “at home, in school, and out of trouble”? Are core child welfare outcomes of safety, stability, and permanency being promoted?

The Wraparound Evaluation and Research team at University of Washington has been thrilled to provide support to several state roll-outs under FFPSA. Similarly, NWIC is aiding states to develop strategic plans that will result in hospitable system and provider contexts for Wraparound, and offering technical assistance and training for the workforce.

If your state has included Wraparound in its FFPSA plan (or is planning to do so), here are a few resources and things to remember with respect to evaluation and implementation:

- Convene state-wide (and local) oversight groups as early as possible that include relevant partners in the effort (leaders from all relevant systems, provider organizations, family and youth leaders, community organizations). This group should collectively design the state strategy and evaluation plan, review data, and make mid-course corrections.

- Consult tip sheets from the Administration for Children and Families and our own NWI guidance for basic ideas.

- To aid in fidelity, satisfaction, and outcomes monitoring, UW WERT’s new WrapStat system and measures of the Wraparound Fidelity Assessment System are well validated and helpful in staying on track.

- Do not hesitate to reach out for help! NWIC and UW WERT are always here to provide assistance on system design, workforce development, and evaluation.

Tribute to Richard Donner

February 24, 2023 | NWI

With the recent death of Richard Donner, we lost a good friend and respected colleague whose vision and commitment were instrumental in building the family movement within children’s mental health. Richard was unwavering in his vision for making family voice and choice a reality.

In the early 1980s – before Wraparound was defined with “family and youth voice and choice” as its first principle, and before “family driven” was an aspiration for systems of care – Richard was a therapist and social worker with a deep commitment to partnering with families. His approach was based on building trust, and showing deep respect for the expertise and perspective that families brought to the table. At the time, this was a radical idea that ran directly counter to mainstream practices in children’s mental health services and systems.

Working in Kansas, Richard became part of the family movement that emerged in the 1980s and grew steadily for decades, eventually inspiring and collaborating with a parallel movement demanding youth and young adult voice in mental healthcare. Richard’s role in the family movement is exemplified by his steadfast support for the development of the Kansas organization, Keys for Networking, and the formation of the National Federation of Families for Children’s Mental Health. Richard was a key figure in early work developing Wraparound, as well as the kinds of supports that families and young people wanted once their voices were empowered, such as respite, peer support and mentoring. He was a voice for change for children, youth and families, helping to make it possible for more young people to live and thrive in their home communities.

— Janet Walker, Eric Bruns and Jane Adams

Update on SMART-Wrap: A Text-Based Fidelity and Outcomes Monitoring for Wraparound

December 10, 2022 | Eric Bruns

Earlier this year, we reported that the University of Washington Wraparound Evaluation and Research Team (UW WERT) and 3C Institute received funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) to develop and test a “mobile Routine Outcomes Monitoring” (mROM) system for Wraparound that collects data from parents, caregivers, and youth using text-based surveys.

SMART-Wrap (Short Message Assisted Responsive Treatment for Wraparound), aims to provide a low-burden, reliable approach for obtaining feedback from caregivers and youth enrolled in Wraparound. Data will be available to care coordinators, supervisors, and managers for use in monitoring fidelity, satisfaction, and outcomes for use in planning for individual families, supervision, and quality assurance for the entire Wraparound program. An initial phase of effort engaged over 70 experts from the National Wraparound Initiative (NWI) community on how the SMART-Wrap System would work, and to identify and develop wording for survey items.

Initial Results and Responses

Working with two Wraparound provider organizations – Region 6 Services of Nebraska and Lutheran Community Services Northwest of Washington State – we conducted an initial round of usability testing with 12 parents and caregivers and five youth served by six care coordinators. Results found that:

- Text messages with linkage to SMART-Wrap surveys were opened 86% of the time and surveys took an average of approx. 30 seconds for youth and caregivers to complete.

- Responses to user surveys were very positive:

- Over 90% of caregiver and youth testers “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that the SMART-Wrap system was easy to use.

- 100% of testers “strongly agreed” that they were “satisfied with the system” and 100% reported it did not take too much of their time.

- SMART-Wrap obtained a mean score of 82% on the System Usability Survey (SUS), a widely used measure of technology acceptability and usability. This far exceeds the 68% benchmark for usability established via research on the SUS.

- Focus groups with parents and youth provided critical feedback for improvement on:

- SMART-Wrap items – parents said satisfaction and fidelity items should specify the time period for feedback, because care coordinator turnover may mean they had varying experiences over time.

- Item wording – youth said to simplify items.

- Response scales – youth suggested using emojis

- Timing of sending surveys – Parents and youth both suggested the system should send texts at more convenient times

- Setting up for success – Parents and youth both recommended care coordinators should help families set the system up in their phone as part of the engagement phase, to explain its purpose and make sure they recognize the sender.

Specific Quotes from Parents

- “I liked doing this. It was quick and easy.”

- “Sometimes I almost disregarded the texts because I wasn’t paying attention and almost mistook them for spam.”

- “It was simple and straight forward I didn’t have any issues at all.”

- “Just knowing that my team is there and if I need help or have question to issue, it helps having other people point of view.”

- “I think it could be a valuable resource if they decide to use it.”

- “To the point and fast to communicate”

Data collected showed reasonably good variability across the 11 SMART-Wrap engagement, satisfaction, fidelity, and outcomes items. See the table below for how responses looked by item for one user testing site.

Next Steps for the SMART-Wrap System and Opportunities to Get Involved

Development of Dashboard and Reporting System

A dashboard and reporting system are now being developed for Wraparound provider organizations that will present data in “real time” to care coordinators, supervisors, and managers, to help them respond to individual families who may be struggling and provide effective support to all families based on data.

Pilot Testing

UW WERT and NWI are now seeking additional SMART-Wrap pilot test sites for a second round of testing from February – June 2023. If you are interested in learning more about the SMART-Wrap system and/or being a pilot test site, we invite you to join us for a webinar on Tuesday January 17 at 2pm ET / 11am PT.

On the webinar, we will provide an overview of the system and how it works, present initial results, and describe how results are informing improvements. We will then present details on how your Wraparound program or initiative can participate in a new round of testing, expectations of sites, and incentives for participants, and answer questions. In the meantime, you can also go to the website for UW WERT to find a summary for interested SMART-Wrap pilot sites.

Have Questions or Want to Be a SMART-Wrap Pilot Site?

To express interest in being a SMART-Wrap pilot site or ask questions, please feel free to contact us at wrapeval@uw.edu and/or ebruns@uw.edu.

Table 1. SMART-Wrap Survey Items and Frequencies from Pilot Test*

| 0 Not at All |

1 Sometimes |

2 Always |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. My care coordinator, Wraparound team and I are all on the same page about what we are working on together. | 2 | 7 | |

| 2. I feel confident my care coordinator will help my family meet our needs | 1 | 8 | |

| 3. My youth and family have made progress since starting Wraparound | 1 | 6 | 2 |

| 4. I am satisfied with how the Wraparound process is working for my family and me so far | 1 | 9 | |

| 5. My youth and family have a team of people that work with us to meet our needs | 2 | 8 | |

| 6. My youth and family helped create a written plan of care that includes our needs and strategies to meet those needs | 3 | 7 | |

| 7. Our Wraparound plan of care is based on the strengths, needs, and preferences of my youth and our family | 2 | 8 | |

| 8. Since starting Wraparound, my youth has made progress that has positively affected their quality of life | 8 | 3 | |

| 9. Participating in Wraparound has helped our family’s quality of life | 4 | 7 | |

| 10. I feel confident I can support and care for my child, now and in the future | 6 | 3 | |

| 11. Participating in Wraparound has increased my confidence that I can manage future challenges that may come up for my family | 3 | 6 |

*Note that youth/young adult survey items are phrased somewhat differently to align with their developmental level and perspectives.