Wraparound Blog Archives - Page 5 of 5 - National Wraparound Initiative (NWI)

Wraparound and the Family First Prevention Services Act

May 14, 2019 | Janet Walker

With states working toward implementation of the new federal law, the Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA), there are new opportunities for using Wraparound to avoid placing children in foster care, to prevent placement disruption for children in adoption and kinship guardian homes, and to meet the mental health, substance use and related needs of at-risk children and their families/caregivers. If Wraparound is included in your FFPSA Prevention Services Plan, you could also use FFPSA training dollars to build provider capacity to deliver fidelity Wraparound and use FFPSA administrative dollars to support data systems, fidelity monitoring, quality and outcomes tracking.

If your state is interested in using Wraparound in its FFPSA Prevention Services Plan, don’t wait to see what ends up getting listed on the Children’s Bureau Clearinghouse. The Children’s Bureau has said repeatedly that they are eager to see what states want and propose for their plans. The Clearinghouse will be reviewing programs as they receive them – especially those submitted by the states – and producing ratings for different programs on a rolling basis.

Bottom line: Go ahead and include Wraparound in your prevention plan, even though it is not yet listed by the Clearinghouse. The more states that include it, the greater the likelihood it will end up on the list.

The NWI has compiled a brief information sheet on Wraparound and the FFPSA. The information sheet includes more information about the FFPSA, as well as information about the research evidence for Wraparound and where you can find Wraparound listed as an evidence-based or promising program.

Adapting Wraparound for Older Youth and Young Adults

January 17, 2019 | Janet Walker

In mid-December, NWI and NWIC staff presented a webinar, and unveiled a new report, on adapting Wraparound for older youth and young adults. There were 660 registrants for the webinar, which provides an indication of interest in this topic. In the webinar, my colleague Caitlin Baird and I presented key findings from a qualitative research project that we had undertaken in the previous year. We wanted to explore Wraparound providers’ views on why and how they might change their practice when working with older youth and young adults. To do this, we sought out Wraparound programs and initiatives from across the nation that serve substantial numbers of young people over the age of 18. From these programs, we interviewed Wraparound facilitators and peer support providers involved in direct service to young adults, as well as managers of the programs. We wanted to address a series of questions, including these:

- What sort of adaptations were providers making?

- Did the adaptations that different providers were making resemble one another?

- How profoundly was practice altered as a result? And

- How systematic was the process of adaptation?

- How were practice quality and fidelity being ensured for the adapted practice?

The webinar and report answer most of these questions. We did find that the adaptations being made across providers and programs strongly resembled each other, which made sense since the adaptations responded to developmental differences between young adults/older youth and younger children in Wraparound. We also found that while practice was adapted significantly, providers were mostly confident that the adapted practice nonetheless adhered to Wraparound principles and fidelity guidelines. However, providers were not so confident about some areas of practice, and wanted clarification, particularly regarding expectations for teams (e.g., membership and frequency of meeting) and timing (e.g., how the phases of Wraparound might look different for youth and young adults). Further, providers were looking for guidance around how to ensure fidelity when practice is adapted.

If you are interested in this topic, I encourage you to read the report and/or view the webinar. Staff at the NWI and NWIC have made plans to follow up on some of the issues described above. We plan to mobilize our experts and develop a learning community to aid us in creating specific guidance around fidelity expectations. This should happen in the Spring of 2019, with a guidance document coming out after that. We will be providing further training and technical assistance during the National Wraparound Implementation Academy in September, and hope to see you there. Rooms at the Academy hotel are going fast!

Pre-Institute on Wraparound Supervision A Success!

September 18, 2018 | Emily Taylor

Approximately 40 Wraparound supervisors from around the country participated in the Pre-Institute Training “Supervision in Wraparound: Moving Beyond the Values and Principles,” one of six intensive two-day trainings held before the before the Training Institutes in July.

In this training, Kim Estep, NWIC Director, and Kimberly “Covi” Coviello, NWIC Assistant Director, challenged supervisors to think deeply about how they can best create a climate and culture that allows for quality Wraparound implementation. Participants walked through operationalization of the values and principles of Wraparound to create clear expectations of their teams.

“This group impressed me with their openness in sharing their experiences with one another, and their focus on learning new skills to take back to their organizations and states,” commented Kim Estep. “From their feedback, I think everyone walked away with renewed enthusiasm for partnering with families in Wraparound and using skill-based supervision for improved outcomes and greater staff satisfaction and retention.”

For those looking for more opportunities for Wraparound training, save the date for the next National Wraparound Implementation Academy (NWIA), September 9-11, 2019 at the Baltimore Waterfront Marriott.

Remembering Jonathon Drake

June 5, 2018 | Eric Bruns

Jonathon Drake

Jonathon DrakeIt is with great sadness that the National Wraparound Initiative announces the passing of a cherished member of its community. Jonathon Drake, 36, a longstanding NWI member and integral part of our national network of champions for youth with complex needs, died on May 23, 2018.

As described in his obituary, Jonathon was a husband, father of two boys, and a man of immeasurable integrity and bottomless kindness. His lifework was as a social worker at the University of New Hampshire’s (UNH) Institute on Disability. He was a Wraparound trainer and coach who focused on the school-based wraparound model called RENEW (Rehabilitation for Empowerment, Natural Supports, Education, and Work), including RENEW implementation for schools participating in the ongoing randomized controlled trial of RENEW funded by the Institute on Education Sciences.

Jonathon’s influence as a champion for youth and schools and his talent for facilitating trainings for school and mental health agency staff was recognized across the state, the country, and even internationally. Appropriately, Jonathon was honored as the first recipient of the New Hampshire Youth M.O.V.E. Rockstar Award in 2016. He was on track to complete his certification as a high school principal alongside his wife in the fall, and it was his dream to lead a New Hampshire high school one day.

For more on Jonathon, see videos of him facilitating a RENEW wraparound process in the influential documentary “Who Cares About Kelsey” at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YvHXZgKqlLs. You can see his profile page at the UNH IOD at https://iod.unh.edu/person/drake/jonathon.

The NWI will be working with UNH IOD on a lasting tribute to Jonathon, such as a scholarship or award in his honor. More information on how members of the NWI and Wraparound communities can donate to the cause will be forthcoming.

Call to the Field from our Colleagues in Puerto Rico – More Spanish Language Materials Needed

May 15, 2018 | Emily Taylor

As part of the NWI mission, we provide information, resources and tools to support Wraparound around the nation and around the world. Although we have been able to provide a Spanish-language version of the Wraparound Process User’s Guide, we recognize that there is a need for more materials in translation, into Spanish and other languages.

Mayra M. Perez Gonzalez

Mayra M. Perez GonzalezThis need was reinforced recently when Mayra M. Perez Gonzalez, an evaluator with PR SOC Initiative III at ASSMC, the Administration of Mental Health and Addiction Services in Puerto Rico, contacted us. She explained that many of her team members and their clients are Spanish speaking, with limited English, so Spanish-language materials would be very valuable.

Since Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico September 20, 2017, life for many of its residents has not returned to normal. After months without power, it is estimated that more than 30,000 residents still have not had power restored. With damage from the storm estimated at $100 billion, many are still waiting for FEMA benefits. Meanwhile, more than 50,000 homes have nothing for roofs but blue tarps. Before Hurricane Maria, more than half of Puerto Rico’s population was already living in poverty. Since the storm, more than 200,000 residents have left the island for mainland U.S. and it is expected that many of them will not return. School enrollment data from six states receiving Puerto Rican children, shows that more than 22,000 children have been enrolled stateside since the hurricane.

These conditions would test the resiliency of anyone and research shows natural disasters can lead to PTSD, depression and suicide. Providers in Puerto Rico are seeing signs of increasing mental health concerns there. And hurricane season for the region starts again June 1.

Mayra wrote to us, "More than ever, I think that we need to implement the Wraparound model to the families in Puerto Rico. We have been surviving by the effort of the community-based groups. And without knowing it, they have been implementing the Wraparound model. Slowly but surely the everyday life has been moving on, especially in our impact area, the west of the island. But this is not the reality for the rest of the island. The power system is very fragile and we are grateful for resources sent to help in that area but still there’s a lot of work to do. And the hurricane season starts soon. We are still working hard to reach our families and their children with severe emotional disturbance. It would be so helpful if we had information in Spanish to easily explain the model."

We are calling on our NWI members and readers in hopes that collectively we can offer Puerto Rico some help in the form of Spanish-language Wraparound materials. If you have materials in Spanish to share, or are able to provide translation services, please contact us.

Increasing Youth Engagement in Wraparound: Findings from a Randomized Study of the Achieve My Plan Enhancement

March 23, 2018 | Janet Walker

This recent article by NWI/NWIC staff and colleagues describes findings from a randomized study in which half the participants got Wraparound “as usual,” and the others got Wraparound together with an enhancement that successfully increased youths’ engagement and active participation in Wraparound, as well as their alliance with the team. We’re pleased to be able to offer the full text of this article on the NWI website!

Here’s a summary of the article, as well as updates on where the AMP project has been up to since the randomized study was completed.

Achieve My Plan (AMP) is an enhancement for existing interventions and programs that is designed to strengthen providers’ skills in key areas that are typically needed for working successfully with youth and young adults. Specifically, AMP focuses on increasing providers’ capacity for working with young people in ways that promote their acquisition of self-determination skills, ensure that care/treatment is based on their perspectives and priorities, and highlight and build on strengths in meaningful ways.

AMP was originally developed and tested as an enhancement to Wraparound, which is a team-based planning and intensive care coordination process. Wraparound is intended to improve outcomes for children, youth and young adults with the highest levels of mental health and related needs, .and their families. Wraparound’s first principle stresses that the process should be built around the priorities and perspectives of the young person and their family; however, in practice, the young people’s “voice” is often not present to a meaningful extent. The AMP enhancement for Wraparound aims to increase young people’s satisfaction, active engagement and self-determined participation in Wraparound, as well as their alliance with their treatment planning team. Findings from a randomized study of AMP showed that, relative to youth who received “as usual” Wraparound, young people who received Wraparound with the AMP enhancement participated more – and in a more active and self-determined manner – with their teams. They also rated their alliance with their Wraparound teams significantly higher. Furthermore, adult team members in the intervention condition rated team meetings as being more productive, and they were more likely to say that the AMP meetings were “much better than usual” team meetings.

Since its initial development, AMP has been used to enhance providers’ practice within other interventions that include a focus on youth/young adult voice, strengths and self-determination. Current research on AMP is focused on documenting the extent to which training impacts providers’ competencies in these areas. Current AMP training is completely delivered via “remote” training and coaching (i.e., via a series of web conferences across several months, and via a secure internet video-based coaching platform) in a way that conforms to best practices. Specifically, to ensure that AMP training will be applied in practice, each group web conference is followed up with individualized coaching that incorporates observation of a provider’s work with young people and the provision of objective practice-focused feedback over time. This approach also allows trainees to learn and practice more basic skills (with coaching and feedback) before moving on to progressively more advanced skills.

Data was gathered from 67 trainees who have taken part in online training and coaching for AMP to date. Findings show significant improvements in trainee competencies for working with youth/young adults as assessed by their practice in video recordings, and as assessed subjectively by the trainees themselves. Trainees were also highly satisfied with the training/coaching experience. What is more, practice fidelity monitoring is organically integrated into the coaching process, so that no additional investment is required to track it.

A Study of Turnover among Wraparound Care Coordinators and Supervisors: Part II

July 17, 2017 | Janet Walker

Part II: Causes of turnover and retention

Part I of this blog post described why our staff at the National Wraparound Initiative (NWI) and the National Wraparound Implementation Center thought it was important to explore the issue of turnover among Wraparound care coordinators and supervisors. That post also described the national survey that we used to gather data about turnover, as well as some of the findings (what types of people responded, caseloads in their Wraparound programs, annual turnover rates, impacts of turnover).

In Part II, we continue on with reporting on some further findings. We asked our respondents to consider a list of possible causes of turnover among Wraparound care coordinators, and to select the ones they thought were "important" causes of turnover in their organization. Respondents were then asked to rank the causes they thought they were important. The chart below summarizes the responses.

As you can see in the chart, three causes of turnover – better job opportunities elsewhere, job stress and demands, and too much paperwork/bureaucracy – were selected by 70-80% of respondents as being important causes of turnover. Among these three causes, better job opportunities elsewhere was selected as the number one cause of turnover by just over 40% of respondents.

Causes of Turnover

The remaining causes of turnover were ranked as important by much smaller numbers of respondents, from around 40% for care coordinator skills not a good match for Wraparound to just over 10% for unfair treatment/feel unwelcome by supervisors or co-workers. However, the disparity between the percentages of respondents endorsing each cause as the number one cause of turnover was much smaller. In other words, while some causes of turnover are seen as important by many more respondents, a fair number of respondents see each cause as the most important one for their organization.

We asked respondents about causes of retention – things that make care coordinators attached to their jobs in Wraparound – in a similar way.

The chart below makes it clear that respondents think Wraparound care coordinators are most attached to their jobs for reasons connected to loyalty and commitments. This includes commitment to the children and families they work with, to Wraparound itself and to their co-workers and their organizations.

Contributors to Retention

When you compare the reasons for turnover to the reasons for retention, the contrast is quite striking. Respondents are saying that care coordinators stay in their jobs primarily because of the intangibles (commitments and loyalty) but are most likely to leave their jobs due to more tangible causes such as the opportunity to get a “better” job or the stress and demands of the care coordinator position.

Finally, we wanted to know if there was a relationship between respondents’ estimates of turnover in their organization and the turnover they reported for that same organization. We were a bit surprised to find only a very weak relationship between the two.

The survey provided us with a good base of information but left us with many questions about the causes of turnover and retention. We are currently wrapping up a series of follow-up interviews with selected survey respondents. Through these interviews, we are learning more in depth about these issues. We plan to present a webinar that summarizes our findings from the interview data in the Fall of 2017, so if you are interested, keep an eye on the website or our newsletter to learn about when that webinar will occur.

This document was prepared with support from the National Technical Assistance Network for Children’s Behavioral Health operated by and coordinated through the University of Maryland, and under contract with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Contract #HH280201500007C. The views, opinions, and content expressed in this presentation do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or policies of the Center for Mental Health Services (CMHS), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

A Study of Turnover Among Wraparound Care Coordinators and Supervisors

June 12, 2017 | Janet Walker

Part 1: Description of the Study and Impacts of Turnover

"Staff turnover in mental health service organizations is an ongoing problem with implications for staff morale, productivity, organizational effectiveness and implementation of innovation, such as the introduction of evidence-based practices." (Aarons & Sawitzky, 2006, p. 289)

Staff from the National Wraparound Initiative and the National Wraparound Implementation Center are in frequent contact with stakeholders from Wraparound programs across the country, and there is no shortage of anecdotal evidence about the negative impacts that staff turnover can have on children and families, as well as on other staff in agencies that provide Wraparound.

The quote from Aarons and Sawitzky sums up the general perception in the field that turnover is an ongoing and serious problem. But surprisingly, there is relatively little research on turnover in human service organizations. The limited research that does exist has found that:

- Public mental health services typically experience turnover rates of at least 20-30%.

- The United States Department of Labor estimates the cost of replacing a worker is at least 33% of annual salary.

- Turnover’s impact on mental health clients has not been well investigated, but is assumed to be problematic.

- Organizational commitment and job satisfaction help to prevent turnover.

- Burnout is the most commonly cited cause of turnover in mental health services organizations, and burnout can be significantly influenced by organizational culture, as well as work-based social and professional support.

When we looked for studies and reports about turnover in Wraparound, we were not able to find enough information to address the many questions we had. For example: Are turnover rates in agencies that provide Wraparound similar to rates for other public mental health services? Is there wide variation in turnover rates, such that some agencies experience much higher and others much lower turnover? And if so, what are the factors that might contribute to that variation? Knowing the answers to these sorts of questions could suggest strategies that might be effective for retaining staff, increasing job satisfaction and, ultimately, contributing to a more experienced and more effective Wraparound workforce.

This line of reasoning led us to undertake a study focused on understanding more about turnover in Wraparound. In the early part of this year, we created an online survey about turnover, and recruited broadly for participants. In the early spring, we closed the study and began to analyze what we’d found. We are currently interviewing some of the survey participants to get a more in-depth description of what they think lies behind turnover and retention in their agencies.

This blog post is the first in a series that will discuss the findings from this research. This post will describe who took part in the survey, as well as their perceptions of the impacts that turnover has. In subsequent posts, we’ll go on to discuss the other findings from the survey and from the interviews.

We collected data during the winter of 2016-17, and got 331 complete responses. Respondents were primarily Wraparound care coordinators, supervisors and administrators. Respondents came from a total of 39 states and most reported that their agencies were located in large or medium metropolitan areas, though there were substantial numbers of respondents from small cities and rural areas as well.

One interesting finding was that more than two thirds of respondents reported that the caseloads for care coordinators in their agencies was 12 or fewer (i.e., in line with recommendations from the NWI), though the remainder reported higher caseloads.

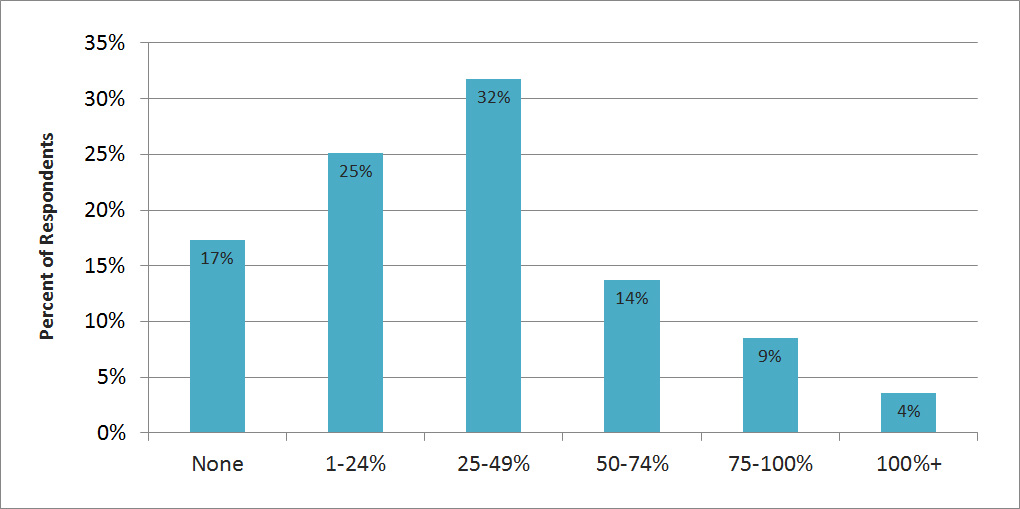

We were somewhat startled to find that the average one-year turnover rate reported by respondents was just about 40%. However, turnover varied widely. Seventeen percent of respondents reported no turnover at all among care coordinators in their agencies during the past year, while almost a third of respondents reported more than 50% turnover. Another third of respondents reported turnover of 25-50%. Respondents also estimated that just under half of the turnover was accounted for by care coordinators leaving during their first year.

Percentage of Wraparound Care Coordinators Who Left their Jobs at Respondents’ Agencies During the Past Year

About 40% of respondents described turnover among Wraparound care coordinators in their agency as a serious problem. When asked about the negative impacts that turnover had, more than 80% of respondents said that turnover was a significant problem because children and families enrolled in Wraparound suffered when their care coordinators changed. Two-thirds of the respondents noted that turnover among care coordinators was a problem because it increased the workload for the remaining care coordinators, and about half of the respondents noted that turnover was problematic because it increased the workload for supervisors. About half the respondents noted that turnover among care coordinators was problematic because the quality of Wraparound provided was lower, and because turnover caused increased costs to the agency for hiring, training and orientation.

| Possible problems caused by CC turnover | % of respondents saying this is a "significant" problem in their agencies |

|---|---|

| Children and families suffer when CCs change | 81.2 |

| Increased workload of other CCs | 66.7 |

| Increased workload of supervisors | 52.1 |

| Lower quality of Wrap provided | 51.8 |

| Training and other costs are higher | 50.2 |

| New people can’t work as effectively with other systems | 30.1 |

| Hard to fit people into the team that provides Wraparound | 15.1 |

Next month, we’ll post more about the findings from the survey, including top reasons for turnover and retention.

What has your experience been regarding turnover among Wraparound care coordinators? Do you think it’s a problem and, if so, do you have ideas about what could be done to decrease turnover? Feel free to leave your comments and thoughts below!

This document was prepared with support from the National Technical Assistance Network for Children’s Behavioral Health operated by and coordinated through the University of Maryland, and under contract with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Contract #HH280201500007C. The views, opinions, and content expressed in this presentation do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or policies of the Center for Mental Health Services (CMHS), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

From Zero to 206 in 25 Years: The Wraparound Research Base Reviewed

May 9, 2017 | Eric Bruns

John Burchard

John BurchardTwenty-five years ago this month, I traveled to Burlington, Vermont to visit the campus of the University of Vermont (UVM), and considered whether to accept its offer of graduate study in community and clinical psychology.

As I learned over the next four frigid years, the sunny, 65 degree weather that greeted me that day was not something I could expect on future spring days in northern New England. What did not disappoint me, however, was my decision that day to work with John D. Burchard, Professor of Psychology at UVM. John ultimately became a mentor, friend, and my greatest role model for leading a principled, outcome-focused career and life.

When I traveled north from Virginia in 1992, John’s paper on Project Wraparound in Vermont was the only published academic paper on what were then called “Wraparound services” for youth with complex behavioral health needs and their families1. John’s trailblazing work inspired me during graduate school to study individualized, family-driven service models, and how systems can invest in such shifts in service delivery. My dissertation was the first-ever controlled study of the impact of respite care.2

As John’s health declined in the early 2000s, John, his wife Sara, and I wrote a chapter on Wraparound in a book Edited by Barbara Burns and Kimberly Hoagwood3. This experience inspired me to come back to Wraparound as a research topic, and find others with whom to further build the research base. By then, over a dozen studies on Wraparound had been published, including a couple of randomized control studies,4 5 and momentum was growing to develop and support new ways to keep youth “at home, in school, and out of trouble.”6

Where is the Wraparound research base now?

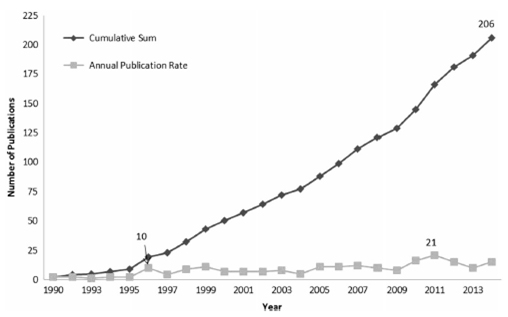

A systematic review of Wraparound research just published in the Journal of Child and Family Studies and led by Jennifer Schurer Coldiron on our University of Washington Wraparound Evaluation and Research Team found that, as of 2014, 206 peer-reviewed publications had been published on Wraparound. Below are just a few of the authors’ findings from this new review:

- The rate of Wraparound research has been accelerating over time. As shown in the accompanying figure, 10 to 20 papers on Wraparound are now typically published every year. It seems that Wraparound is far from a passing fad, as was a concern around the turn of the millennium.

- Wraparound has been the subject of 22 controlled studies, 15 of which showed positive results of Wraparound compared to the control or comparison condition. Although several studies found no differences between conditions, none of the 22 studies found better outcomes for the comparison group.

- Implementation quality and fidelity measurement has only become commonplace among published outcomes studies in the last few years. Among studies that found null results and actually measured implementation quality, lack of adherence to the Wraparound model was typically a main reason Wraparound did not improve outcomes over services as usual.

- Relatedly, an emerging body of research is demonstrating the importance of adhering to specific principles of Wraparound care in order to achieve outcomes. Research is also finding that without achieving certain types of program- and system-level standards (e.g., caseloads, training and supervision, funding flexibility), youth and system-level outcomes are likely to suffer.

- Cost-effectiveness studies are not typically conducted with rigor; however, several such studies7 make a compelling case for Wraparound’s ability to dramatically shift service use patterns toward more community based care and reduce overall costs of services.

- Eighty-four of the 206 papers on Wraparound were non-empirical “thought pieces” that described the practice model or made the case for Wraparound. Interestingly, the proportion of non-empirical papers published every year does not seem to be declining over time. We speculate that Wraparound’s capacity to serve as an “operating system” for coordinating care for many types of individuals and system contexts has led authors to continue to propose new and novel applications of Wraparound for people with complex needs. Of course, it could also be that youth- and family-driven, strengths-based care is still viewed as a “fringe” idea, one that requires continued advocacy.

Despite the growing number of publications, the review also found many gaps in our understanding that point to an array of research studies left to be done. Some topics that need more attention include:

- More on Wraparound’s mechanisms of positive change. As the human services field shifts increasingly toward system-level integration, Wraparound has a lot to offer the conversation about what care coordination practices are most important to achieving outcomes. Our team has proposed that practice elements such as being youth- and family-determined, individualized, and needs- and outcomes-based are applicable to any type of care management model, at any level of intensity. Research that explores this assertion more rigorously and systematically could greatly aid the development and support of care coordination models in all types of health care settings.

- Relationship of the service array to outcomes. While some pilot studies have asked about how best to integrate evidence-based clinical practices and Wraparound8, little rigorous study has asked about the impact of investing in specific types of services or workforce development for staff in other provider roles. Given how little attention many systems of care pay to the breadth or nature of formal services in the continuum of care, such research may help provide guidance – and motivation – to do so.

- Implications of policy, financing, staffing, administrative, and system conditions. Our National Wraparound Implementation Center (NWIC) has now provided training, coaching, and system-level technical assistance to over 10 states. As a result, we have data that indicates certain types of system structures (such as Care Management Entities9) are associated with better youth and family-level practice. Much more understanding in this area is needed to help guide system-level reforms and refinements in states and communities.

- Workforce Studies. With help from nationally renowned trainers and experts, NWIC has developed a sophisticated training, coaching, certification, and implementation support model that uses data to adjust over time. However, even we cannot be sure how best to continue to evolve this model, or how much effort is worth investing in what areas, without more rigorous research on topics such as supervision, data-informed coaching, staff selection, staff training, and methods of providing technical assistance.

- More on family and youth peer support. Remarkably, given our dedication to being youth and family driven and to incorporating youth and parent peer support wherever possible, only three of the 206 studies focused on this topic.

Although the Wraparound research base – and research base for care coordination more generally – would benefit greatly from additional study, Coldiron, Bruns, & Quick (2017) nonetheless concluded that the Wraparound literature produced to date has provided a wealth of useful information. It has explicated and tested (somewhat) Wraparound’s theory and core components, its program and system supports, and applicability across systems and populations. It has begun to unpack relations among system, program, and practice elements and outcomes.

Most important perhaps, the review suggests that we now have a reasonable basis for concluding that, when implemented well, and for an appropriate population, Wraparound is likely to produce positive youth, system, and cost outcomes. In short, Wraparound is research-based. We think John Burchard would be pleased to see how far Wraparound – and those who have endeavored to provide it and promote it – have come.

Figure 1. Annual and Cumulative Wraparound Publications

We invite you to read this review of research, and to let our team at the National Wraparound Initiative know if your Wraparound initiative or system of care provides an opportunity for us to answer any of the above questions. In the meantime, be on the lookout for future installments of this Wraparound Blog, from the National Wraparound Initiative and its many collaborators.

1. Burchard, J. D., Clarke, R. T., Hamilton, R. I., & Fox, W. L. (1990). Project Wraparound: A state-university partnership in training clinical psychologists to serve severely emotionally disturbed children. In P. R. Magrab & P. Wohlford (Eds.), Improving psychological services for children and adolescents with severe mental disorders: Clinical training in psychology. (pp. 179-184). Washington, DC US: American Psychological Association.

2. Bruns, E.J. & Burchard, J.D. (2000). Impact of respite care services for families with children experiencing emotional and behavioral problems and their families. Children’s Services: Public Policy, Research and Practice, 3(1), 39-61.

3. Burchard, J. D., Bruns, E.J., & Burchard, S.N. (2002). The Wraparound Process. In B. J. Burns, K. Hoagwood, & M. English. Community-based interventions for youth (pp. 69-90). New York: Oxford University Press.

4. Clark, H. B., Lee, B., Prange, M. E., & McDonald, B. A. (1996). Children lost within the foster care system: Can Wraparound service strategies improve placement outcomes? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 5, 39-54. doi: 10.1007/BF02234677

5. Evans, M. E., Armstrong, M. I., & Kuppinger, A. D. (1996). Family-centered intensive case management:

A step toward understanding individualized care. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 5, 55-65.

6. Rosenblatt, A. J. (1993) At home, in school, and out of trouble. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 2, 275-281. doi:10.1007/BF01321225

7. Grimes, K. E., Schulz, M. F., Cohen, S. A., Mullin, B. O., Lehar, S. E., & Tien, S. (2011). Pursuing Cost-Effectiveness in Mental Health Service Delivery for Youth with Complex Needs. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 14(2), 73-86.

Humboldt County Wraparound Unit in the News

April 7, 2017 | Emily Taylor

The local Times Standard newspaper in Eureka, Calif. recently highlighted the Humboldt County Wraparound Unit for its work with local at-risk youth. In April 2016 Children and Family Services staff there began training as Wraparound coordinators and coaches, and since then several staffers attended the National Wraparound Implementation Academy and received additional training provided by National Wraparound Implementation Center last fall.

The Wraparound unit team members included in this photo published with the original article, are (from left): Tim Johnson, Candice Campbell, Marshall Boyett, Heidi Young, Trevlene Blood, Donna Filippini, Dani Widmark and Corina Keppeler.

![Pre-Institutes group [click to view full size in a new window] Pre-Institutes group](https://nwi.pdx.edu/images/PreInstitutes-group-standing.jpg)

![Kim Estep and Kimberly Coviello at the Pre-Institutes [click to view full size in a new window] Kim Estep and Kimberly Coviello at the Pre-Institutes](https://nwi.pdx.edu/images/Kim-Estep-and-Kimberly-Coviello-PreInstitutes.jpg)

![Causes of Turnover [click to view full size in a new window] Causes of Turnover](https://nwi.pdx.edu/images/chart-causes-of-turnover.jpg)

![Contributors to Retention [click to view full size in a new window] Contributors to Retention](https://nwi.pdx.edu/images/chart-contributors-to-retention.jpg)

Leave a Reply